Anti-Semitism is the world’s “longest hatred,” the “devil that will not die.” Although the phenomenon has clearly diminished in the United States, it is rampant in the Muslim Middle East, still dangerous in the former Soviet Union, and experiencing a startling resurgence in Europe, the very site of the Holocaust.

Northeastern will tackle the topic in a new course, “Anti-Semitism in 20th-Century American Literature and Film,” The course will offer a full and detailed examination of Judeophobia in American popular culture from the moment Jews first stepped foot onto American soil in 1653 to the current debate over the often subtle distinctions between being anti-Israel and being anti-Semitic.

I have chosen to teach this course at least partly as a result of my personal experience. As a Jew, born and raised during the years of the Holocaust, I have been affected by the issue of anti-Semitism all my life. At the age of 8, I saw photographs of concentration camp victims bulldozed into mass graves. As a college student in the 50s, I was refused membership in fraternities because of national clauses banning Jews.

Entire residential areas near the suburban town in New Jersey where I lived openly “restricted” Jews from living there. During a 10-day prison sentence in New Orleans, guards threatened my life because I was a “New York Jew coming down South to cause trouble.” I visited Auschwitz in 1966 and saw a suitcase in a glass exhibit with my name on it. I drove 2000 miles through the Soviet Union and visited Babi Yar in the Ukraine where 85,000 Jews were slaughtered in three days. I visited the Ukrainian city of Zhitomir, my grandparents’ birthplace. They fled relentless pogroms, allowing me to be born into a middle-class home in New York City instead of ending up in a small pile of ashes at Auschwitz.

A lifetime of sensitivity to anti-Semitism led me to immigrate to Israel after the Six Day War. I taught over 500 students at Tel Aviv University, experienced the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and, one year later, served in the Israeli Army in a special immigrant unit.

Yet, I find students today have rarely experienced direct anti-Semitism, and many have little or no knowledge of America’s 300-year history of anti-Jewish discrimination, insult, threat, accusation, exclusion, rejection, and outright violence. I hope the course I teach at Northeastern will begin to rectify that. We’ll learn about the Christian ethnic gangs, for example, who preyed upon Jews in cities throughout America. In the city of Boston, they beat young Jewish boys going to and from school or who had ventured outside their neighborhoods. A mob in Georgia lynched Leo Frank, who had been unjustly accused of murder, simply for being a Jew.

Fascism and Nazism were endemic in the United States throughout the 1930s and 1940s, as evidenced by Fritz Kuhn’s German-American Bund, William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts, and the anti-Semitic ranting of Catholic priests such as Father Coughlin and Father Feeney in Boston. George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party still has significant influence on dangerous Aryan movements in America.

Anti-Semitic attitudes in America in the 1920’s led to the passage of the Anti-Immigration Act of 1924, an act that was not rescinded until 1965. Many Jews could have been saved from the Holocaust had America opened her gates to desperate victims of Hitler’s genocide, but, tragically, the Justice Department used the 1924 statute to limit immigration.

Popular culture seems a good way to introduce students to this history. Naturally, anti-Semitism found its way into American literature and film. Great American writers in the early part of the 20th Century were unembarrassed by their anti-Semitic feelings and did not hesitate to create anti-Semitic literary characters: Edith Wharton’s Rosedahl in The House of Mirth, , Fitzgerald’s Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby, and Hemingway’s Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises, to name but a few. During the early part of the course, we will analyze and discuss these portraits.

We will also analyze Sylvia Plath’s poem, “Daddy,” one of the great American poems of the century, which makes startling use of the Holocaust as a metaphor for a non-Jewish poet’s private agony.

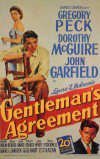

Much of the course will focus on American Jewish writers and filmmakers and their efforts to respond to anti-Semitism through their particular literary and cinematic genius. We will read and analyze short stories, essays, and plays by Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, Arthur Miller, Cynthia Ozick, David Mamet and Nathan Englander. We will watch and analyze key scenes from American films such as “Gentleman’s Agreement,” “Crossfire”, “The Pawnbroker,” “School Ties,” “Annie Hall,” The Believer,” ”Schindler’s List,” “Knocked Up,” “Keeping the Faith,” and “Homicide.”

Students today should be aware of the history of anti-Semitism in America. It is impossible to have a full and meaningful understanding of our culture without it. I believe that the most effective access to this history is through reading and viewing works of art that confront this ongoing world tragedy with aesthetic and visceral power. Ideally, this course will provide that opportunity.