Feature image caption: Aerial view of Colectiva SJF’s installation of names of victims of feminicide in the Zócalo, Mexico City. Courtesy of Colectiva SJF. Photo by Santiago Arau.

The NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks in collaboration with the Digital Scholarship Group, College of Arts, Media, and Design (CAMD), and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (WGSS) Program hosted MIT professor and CAMD affiliate Catherine D’Ignazio to discuss her forthcoming book, Counting Feminicide: Data Feminism in Action (MIT Press 2024). Exploring the innovative and engaging activism in data science in this project, D’Ignazio detailed the continuation of her work with Lauren Klein from Data Feminism (which she and Klein presented on in 2020 for the NULab) to her current collaboration and work with Data Against Feminicide (Datos Contro el Feminicidio).

D’Ignazio began her presentation foregrounding the significant scholarly conversations this project engages with and the theoretical contributions it puts forth in the ecology of critical data studies, an emerging field which interrogates how data (and systems from collection to creation) exacerbate and perpetuate existing systems of social inequities. She is inspired by work in this field by scholars like Safiya Noble (Algorithms of Oppression), Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism), Virginia Eubanks (Automating Inequality), Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias (The Costs of Connection) and Ruha Benjamin (Race After Technology) who analyze and critique existing facets of mainstream data science. Hegemonic data science, to D’Ignazio, works to concentrate wealth and power, accelerates racial capitalism, perpetuates patriarchy, sustains settler colonialism, and exacerbates environmental excesses and social inequality.

On the other hand, critical data studies does not just describe and critique bad practices in data science but also creates counter-hegemonic strategies and actions with data, knowledge, and power. Counting Feminicide extends this project by looking at how people are already doing work of justice and liberation within the feminicide data community. D’Ignazio stated the definition of feminicide as the “murder of a woman or a girl for reasons relating to her gender,” including “intimate partner violence, family violence, organized crime violence, induced suicide, racialized violence, homophobic violence, and more.” Specifically, D’Ignazio asks: what can we learn about challenging data power by looking at grassroots movements and activists across the Americas?

In her presentation D’Ignazio outlined three types of data that data organizations and activists work with: official data are data produced by the state, international institutions and governing bodies; missing data are data neglected by institutions despite political demands that it should be collected and made available; and counterdata are produced by civil society to counter missing data or challenge official data. Together, these types of data underscore central components of D’Ignazio’s definition of counterdata science, a specific form of data activism that centers using and creating data to address issues or cases of missing data in official institutional data, often appropriating conventional data practices to produce knowledge and encourage action outside official routes.

The guiding project behind Counting Feminicide is a collaboration between D’Ignazio, Helena Suárez Val, and Silvana Fumega for Data Against Feminicide (Datos Contra el Feminicidio), a group committed to developing tools, fostering an international community of practice, and supporting efforts for feminicide data production. Data Against Feminicide helps to support and sustain the ongoing efforts of activists. Following the murder of two young women in Argentina in May 2015, the lack of data on feminicide reached national and international attention with calls to action leading to a massive uprising in Buenos Aires and protests spreading throughout Latin America and the world, all aggregated under the hashtag #NiUnaMenos, or “not one (woman) less.”

An example of efforts that sprang up in response to the missing data D’Ignazio classifies is Maria Salguero’s work to map individual cases of feminicide in Mexico in her project “”Yo te nombro: El Mapa de los Feminicidios en México” (“I name you: The Map of Feminicides in Mexico“). Salguero spends hours each day looking for cases, verifying information, and sifting through her network of tips. Following the international wave of attention to feminicide, the United Nations called for the establishment of a feminicide observatory in every country in 2017.

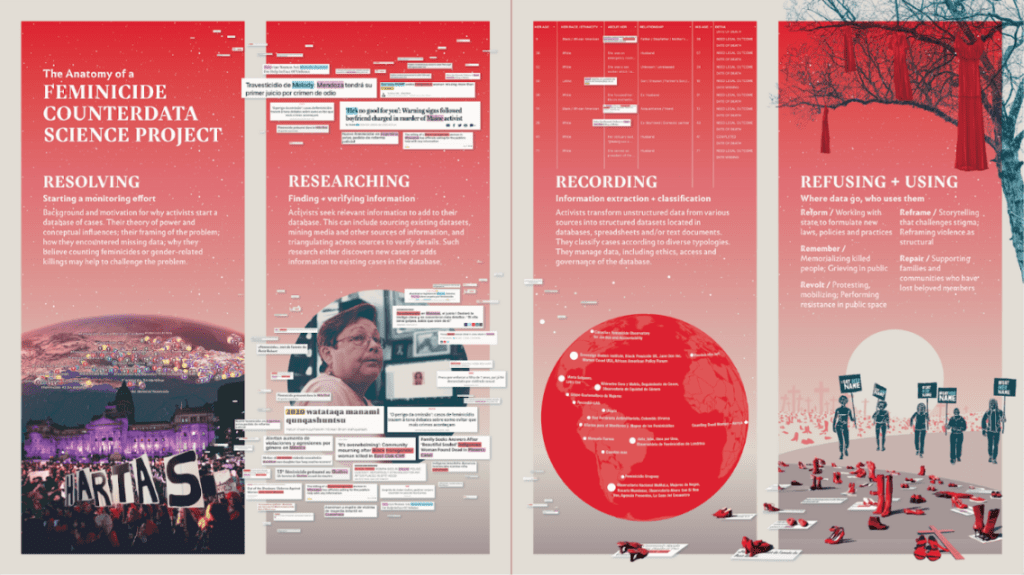

Data Against Feminicide is an ongoing project that has three main pillars: 1) a qualitative research project that cataloged more than 150 projects and interviewed 35 groups engaged in feminicide data collection; 2) a participatory design project; and 3) a community of practice that is global and continually growing. Counting Feminicide explores the qualitative research project in which D’Ignazio and the Data Against Feminicide team gathered information from grassroots organizations and activists on how they define feminicide, their sources of information, software, taxonomies, data collection processes, and more. From this project D’Ignazio offers four stages of counterdata labor with empirical examples in her book: 1) resolving (starting a monitoring effort) , 2) researching (finding + verifying information), 3) recording (information extraction + classification), and 4) refusing/using (where data go, who uses them).

These stages to counterdata labor are not chronological or even congruent, but offer a way of classifying and describing data activist labor.

- Resolving covers the stage in which projects consolidate their motivations for activism and monitoring efforts. While motivations vary, this stage highlights how groups refine their theories about power and how they plan to integrate data into a theory for change. For example, D’Ignazio outlined the work of La Red Feminista Antimilitarista working to develop their own framework of neoliberal feminicidal violence.

- Researching describes the ongoing work of data collecting, finding new cases, and discovering and verifying information. As projects and groups refine their strategies for data collection, patterns emerged in organizations’ practices in how to contend with missing data or how to develop communities to cover larger areas. In particular, D’Ignazio emphasized this stage also includes research and establishing emotional labor and collective care strategies.

- Recording includes the work of extracting unstructured data in data collection and turning it into some kind of structured data (complete with typification and classification), as well as discussion of data ethics, access, and governance. D’Ignazio emphasized that activists find data standards useful, but often produce their own categories local to their context.

- Refusing/Using details the stage in which activists and groups circulate and push data into the public to make change or engagement. This work is both an act of using data as a tactic in a larger struggle, but also refusing quantification amidst systems that perpetuate harm. The tension that emerges here is central to this work. Themes that emerged in this stage include repair, reframe, remember, revolt, and reform.

D’Ignazio ended her presentation with a glimpse into the rest of Counting Femincide including a counterdata science toolkit for rethinking data in every domain so that we can continue to do this work across enduring systemic inequalities. While she built on the central theme of the collective nature of this project, D’Ignazio finished with a caveat from Paola Maldonado from the Alliance for Monitoring and Mapping Feminicides in Ecuador: “We play a minimal role in this process […] this is collective work, networked work, work that it has to continue expanding upwards, downwards, towards all the edges that we can give it.” For D’Ignazio this project has been a lesson in the necessity of collecting and aggregating information about these projects, but also of putting data science and counterdata science in its place as part of larger struggles. As a community of scholars invested in data activism at Northeastern, D’Ignazio’s presentation was an informative look at forthcoming research and a useful model of community practice in academic work to bring together critical theoretical interventions and practice.

If you are interested in further reading and engaging with D’Ignazio’s exciting work from this project, the book manuscript is currently under community review until December 22, 2022 on the MIT Press website. D’Ignazio is committed to community collaboration throughout this process and invites the academic, data science, and feminicide data communities for further feedback and collaboration as this book project continues.

A recording of the presentation is available through Northeastern’s Digital Repository Service.

Image caption: The Anatomy of a Feminicide Counterdata Science Project is a process model that describes the high-level workflow stages that data activists engage in to monitor feminicide. The graphics highlight individual and groups of data activists, as well as the multidisciplinary counterdata science methods used in social movements across the Americas, including #SayHerName, #NiUnaMenos, and #MMIWG2.

Pictured include: Protesters in Buenos Aires, 2015, with signs reading “HARTAS” (“FED UP”) and the city’s Palacio del Congreso lit purple for the now-annual and multi-city #NiUnaMenos public demonstration; María Salguero’s map of feminicides in Mexico (2016–present), viewed on Google Earth; Carmen Castelló, a retired social worker who produces the most reliable data on feminicide in Puerto Rico while she cares for her grand-niece Alba and other young relatives; recent news headlines of reported feminicides from around the Americas in Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, Quechua; a database by Dawn Wilcox from Women Count USA, who spends many hours seeking photos of killed women for it; a map of counterdata activist groups created by the Data Against Feminicide initiative, to support and sustain the practices of activists caring for femicide data in their own contexts; one of many installations of The REDress Project (2010–present) by artist Jaime Black, with each dress representing one of the thousands of missing or murdered Aboriginal women across Canada; the music video for “Say Her Name (Hell You Talmbout),” commissioned by the African American Policy Forum and performed by Janelle Monáe and Black women activists, to raise awareness about the Black Women victims of police brutality and anti-Black violence in the U.S.; one of many installations of Zapatos Rojos (2009–Present) by artist Elina Chauvet, where each shoe represents one victim of feminicide, started in Cuidad Juárez, Mexico; and pink crosses, which started in Juárez as a symbol of justice for victims—many of whom work in low-wage, dangerous factory jobs—but have now transcended borders.

Courtesy of La Nación. Photo by Fabian Marelli. [pending] Courtesy of María Salguero. Courtesy of Dawn Wilcox / Women Count USA: Femicide Accountability Project. Courtesy of Ana María Abruña Reyes / Todas. Courtesy of Jaime Black. Photo by J. Addington. Courtesy of African American Policy Forum. Song performed by Janelle Monaé feat. various artists. Video by 351 Studio.Graphic design by Melissa Q. Teng.