Commencing the DH Open Office Hours for this academic year, Melissa Schlecht—a NULab/DSG Visiting Scholar from the University of Stuttgart—presented her project, “Eruptive Art: The Depiction of Atmospheric Anomalies after Major Volcanic Eruptions in American Artworks of the 19th Century.” Inspired by a 2004 article by Norwegian astronomer Donald W. Olson which proposes that the iconic sunset of Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream was caused by atmospheric anomalies following the 1883 eruption of the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa, Schlecht investigates the influence of volcanic eruptions on atmospheric conditions and artistic production in the United States.

Beginning with an overview of the major volcanic eruptions in the nineteenth century—including the eruption of Krakatoa, Tambora, and Babuyan—Schlecht discussed the effects of the sudden increase of ash and sulfurs in the atmosphere. In the months following eruptions, volcanic aerosol clouds caused unusually intense sunrises and generated scientific and artistic attention across the globe, including a report published by the English Royal society in 1888 on the matter. To investigate the impacts of Krakatoa on artistic productions, Schlecht focuses on artwork created in New England and New York and, following methods used in a survey of volcanic art by Christos Zerefos and his team, examines paintings’ red to green ratios as a sign of atmospheric conditions.

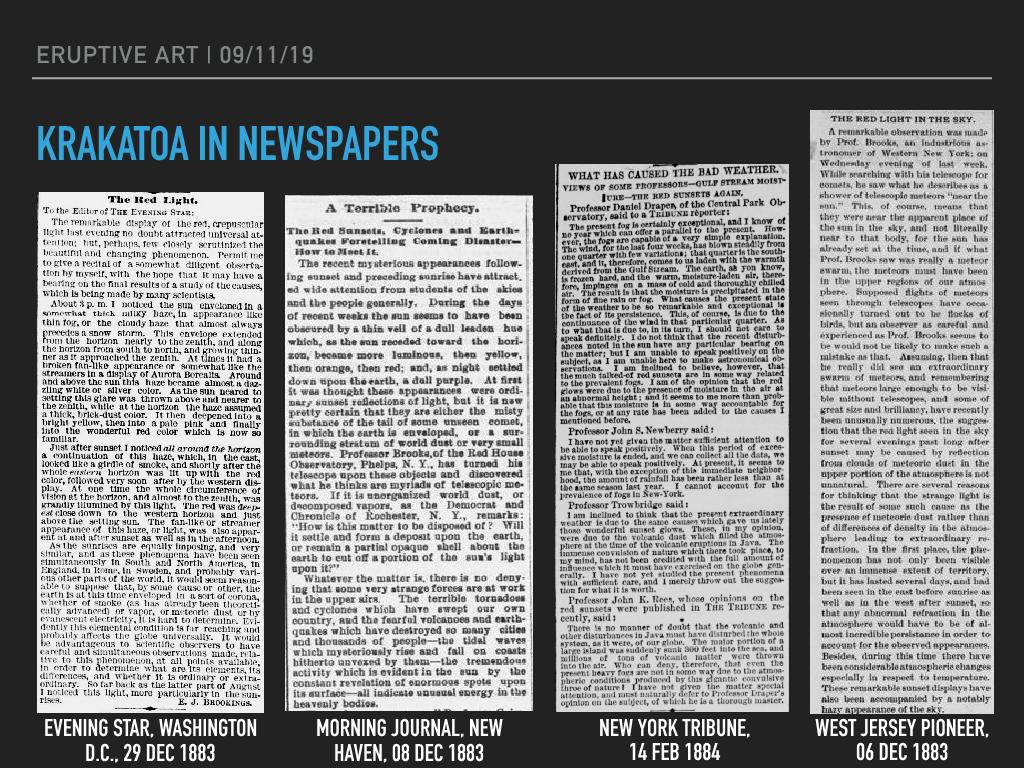

For this project, Schlecht pairs digital humanities and art history by examining newspaper articles from Chronicling America for eyewitness accounts of atmospheric anomalies between October 1883 and December 1884, using these dates and locations to find relevant paintings. In particular, she is interested in two phenomena: the fiery, red sunsets and a strange, yellow (almost green) haze. Scouring the digital collections of museums across New England, Schlecht has so far discovered many works that match these descriptions, including the work of tonalist Edward Michael Bannister and pastel artist Frederic Edwin Church. Bannister’s artwork features bright sunsets in Providence, Rhode Island with a high ratio of red pigments, especially in his landscape paintings between 1883 and 1884.

Throughout her presentation, Schlecht considered the challenges of using digital humanities methodologies with art. Beyond the differences in color that occur naturally with the deterioration and discoloration of pigments over time, Schlecht explained that color distortion is also a serious consideration in modern photography. While many museums have digital collections online, not all photographs of artwork are “colortrue,” or adjusted to resemble the colors of the physical painting. As part of her time in Boston, Schlecht has been taking photographs at museums of paintings related to her project, painstakingly matching the colors in real-time to get the best data for her research.

Schlecht’s project sits at an interesting intersection of DH and art history where digital methods pose significant questions for her discipline. In looking at the connection between atmospheric anomalies and artistic production, Schlecht asks, are these paintings an expressions of artistic style or an accurate depiction of the artists’ surroundings? And, what if the effect of natural events were far more influential on cultural production than has been previously understood? How might this change our understanding of cultural and artistic productions? In the end, Schlecht’s exciting research demonstrates the ways that digital methods bring new perspectives across disciplines in potentially eruptive ways.

Melissa Schlecht is a visiting scholar hosted by the NULab and Digital Scholarship Group as part of the Oceanic Exchanges project. She is a research assistant in the Department of American Studies at the University of Stuttgart, Germany, and is working on her dissertation on American Künstlerroman, focusing on social mobility and cultural capital.