Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic

This module give writers tools to compose personal healing narratives, to frame their personal inquiries within a larger research context, and to position themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through this public teaching initiative, we ask “How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience?”

Living through the current pandemic is not only about the medical and financial fall-out of COV-SARS-2 and COVID-19 illness, but also about the lasting trauma that has been felt by individuals as they, their families, and communities struggle during this historical time. Storytelling is a means of healing from trauma. This module give writers tools to compose personal healing narratives, to frame their personal inquiries within a larger research context, and to position themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we draw upon research on trauma theory, research on expressive writing and healing, and research on responding to writing. Through this public teaching initiative, we ask “How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience?”

- any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s attitudes, behavior, and other aspects of functioning. Traumatic events include those caused by human behavior (e.g., rape, war, industrial accidents) as well as by nature (e.g., earthquakes) and often challenge an individual’s view of the world as a just, safe, and predictable place.

- Any serious physical injury, such as a widespread burn or a blow to the head. —traumatic adj.

All the modules in this series are based on the following four principles of trauma-informed care and teaching:

Connectedness–valuing of relationships

Protection–ensuring safety and trustworthiness

Respect–promoting choice and collaboration

Hope–Resilience and Change

(Adapted from Hummer, Crosland, & Dollard, 2009)

Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic includes the following components:

- Three complementary sessions with resources and activities that explore writing about trauma and responding to writing from multiple perspectives:

- The personal entry point with personal written and oral healing narratives

- The inquiry entry point for writers who want to pursue self-generated research inquiries related to Covid-19

- The community entry point, which supports writers as they position themselves within larger community responses to Covid-19

- A comprehensive online bibliography on trauma, writing, and response

This module was created as part of Northeastern University’s College of Social Science and Humanities Pandemic Public Teaching Initiative. The Pandemic Teaching Initiative, which is supported by the CSSH Office of the Dean, the Northeastern Humanities Center, the Ethics Institute, the SPPUA and the NULab, seeks to create a library of publicly accessible modules that explore topics related to pandemics and their disruptions and impacts.

All of the prompts will generate material that will be shareable, if participants wish, during an open, online event series.

Caution

We have attempted to limit traumatic content in the main text of this module, but the examples used in the following modules may be disturbing for some individuals. Examples include sexual violence, racism, COVID-19 illness, and death.

This session offers an overview of expressive writing and storytelling as a means of healing. This session follows four steps:

- Identify the basic research supporting expressive writing

- Identify narrative strategies and discuss examples of types of healing narratives to help you better understand the narrative techniques and strategies you will learn.

- Complete informal writing prompts that offer you the opportunity to begin applying these strategies to your own writing.

- Use informal writing prompts to build towards a full-length healing narrative and recognize elements of effective feedback.

- Reading: Chip Scanlan, “What is Narrative, Anyway?,” Poynter

This session offers an overview of expressive writing, which is writing that pairs emotions with events and action with reflection. It also offers some of the research into writing about trauma as a means of healing, as well as examples of published written and oral healing narratives. This basic grounding in the literature of expressive writing and healing will support the specific narrative entry points for writers that appear in subsequent modules.

Expressive writing is a specific type of narrative writing that combines experiences with reflection and insight. Often, we’re more familiar with straight journaling or chronicling events in a diary, but it is the interplay between emotions and events and the ability to distinguish feelings from the past and the present in expressive writing that distinguishes it.

Expressive Writing

- Does more than simply record events

- Does more than simply vent feelings

- Includes action and reflection

- Includes descriptive and/or figurative language

As defined by Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing, 2000, Chapter 2.

- Video: The Expressive Writing Method

- Video: What Does Expressive Writing Look Like

- Reading: Oliver Glassa, Mark Dreusickea, John Evansa, Elizabeth Becharda, and Ruth Q. Wolever, “Expressive Writing to Improve Resilience to Trauma: A clinical Feasibility Trial,” Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice

- Reading: James W. Pennebaker, “Expressive Writing in Psychological Science,” Perspectives on Psychological Science

- Reading: Kimberly Mack, “Johnny Rotten, My Mom, and Me,” Longreads

- Reading: Tracy Strauss, “Writing Trauma: Notes of Transcendence,” The Ploughshares Blog

- Reading: Ann Wallace, “A Life Less Terrifying: The Revisionary Lens of Illness,” Intima

- Podcast: My Brain Explosion

- Questions to Consider:

- Once you’ve read the essays and articles and watched the two videos that accompany this session, think about how expressive writing is different from other types of writing you may have done (journaling, expository writing, etc.) What do you see as the biggest opportunities and challenges of this type of writing?

In this session, you will learn about three specific types of wounded body/healing narratives as classified by Louise DeSalvo: the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative. The suggested readings offer elements of these types of healing narratives. In addition, the Strauss piece offers a useful frame for how to pair emotion with reflection/insight in expressive writing, which you will be able to apply to your own writing in the next session.

- Reading: Alison Rosalie Brookes, “Love and Death in the time of Quarantine,” Health Story Collaborative

- Reading: Nina Collins, “Graduations,” Intima

- Reading: Tracy Strauss, “Writing Trauma: Notes of Transcendence, #4—The Situation and the Story,” The Ploughshares Blog

- Reading: Jennifer Stitt, “Will COVID-19 Strengthen our Bonds?,” Guernica

- Reading: Adina Talve-Goodman, “I Must Have Been That Man,” Bellevue Literary Review

- Reading: Jesmyn Ward, “On Witness and Respair: A Personal Tragedy Followed By a Pandemic,” Vanity Fair

- Types of Healing Narratives/Wounded Body Narratives Tip: Often, healing narratives have elements of more than one of these frameworks—for example, particular passages in a quest narrative may take on the immediacy and visceral feel of a chaos narrative. You will likely identify elements from more than one of these frameworks in the published essays in this session.

- Questions to Consider:

- Once you’ve looked at the chart above and the accompanying essays, think about which types of healing narratives (chaos, restitution, and quest) you would characterize them. Which essay or essays resonate the most with you, and what narrative elements/strategies account for that–can you point to specific moments in the text?

In this session, you can apply what you’ve learned about different types of healing narratives and from the sample published essays to formative writing activities. Please choose as many of these short, informal writing exercises as you would like, keeping in mind the fundamentals of expressive writing, i.e., linking emotions with events. Start with 15 minutes on a prompt and see how far you get.

Activities:

- As Ann Wallace asks in “A Life Less Terrifying,” write a journal entry about a time when you were denied some kind of essential or fundamental human need—love, compassion, respect, dignity, shelter, the possibilities are many. If you’d like, you can focus this within the context of COVID-19 and your experiences living through it.

- Thinking about a time you were denied a fundamental need, now try writing a letter to someone as a means of telling this story. Think about the differences in your story that arise when you address this towards an intended reader.

- Draw a map of a meaningful landscape from your COVID-19 experience (e.g., where you’ve spent the most time) including as many details as possible. Think about 2-3 specific memories/events that have taken place in that space, and make a list of as many sensory details as possible–what sounds, smells, touch, images, etc. do you associate with this place and these memories? Use this sensory list to start writing about your experiences during COVID-19.

- What family story or generational tale do you wish had a different ending? What would it look like? Alternatively, what COVID-19 story would you re-write if you could?

Looking for additional short prompts specific to COVID-19? Check out The Pandemic Project, directed by James Pennebaker.

Optional revision activity:

Have a response to a writing prompt you want to deepen? Consider using Strauss’s Situation and Story essay for the following activity: Make a two-column chart where you identify the actions/plot points in your narrative (the situation) and a column where you reflect on the emotions of the event (the story). This will help highlight places where the pairing of emotions with events and action with reflection could be developed.

We’ve discussed the different kinds of wounded body narratives classifications (the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative), and have read a variety of healing narratives that deal with trauma, loss, illness, etc. To draft your own healing narrative, take these three frameworks and the formative writing you’ve done in Session 1.3 surrounding this denial of a fundamental need as a foundation for a longer essay where you explore a seminal event or trauma in your own life. If you would like to focus this writing on events related to COVID-19 you may, but you are not limited to that. As you write, think about the qualities of healing narratives DeSalvo mentions, and the characteristics/criteria for successful healing narratives included in this session. Above all, healing narratives pair emotions/feelings with events.

Once you’ve drafted your healing narrative using the prompt above, we recommend getting feedback on it so you can continue to deepen and order the draft.

Getting feedback on your healing narrative:

You might find that you want to share your narrative with someone you trust or even present your narrative in a public forum. Before you share your work, however, you want to think about the feedback you may receive. If you simply ask a friend to give you feedback on your narrative, they may give you bad advice. For example, they may only tell you about grammatical errors or, worse yet, debate the content of your narrative.

Because most readers are not familiar with healing narratives, it’s useful to give them some guidance on how to respond to your writing. Two tips are helpful here:

1. Content-based response. Based on the research and work of Louise DeSalvo, ask readers to focus on the following characteristics of effective healing narratives.

Elements of a Healing Narrative

- Renders our experience concretely, authentically, explicitly, and with a richness of detail

- Links feelings to events, including feelings from the past versus feelings in the present

- Is a balanced narrative that uses negative words but also includes the positive and that continues to evolve

- Reveals the insights we’ve achieved from painful experiences

- Tells a complete, complex, coherent story that can stand alone and can take multiple forms

Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Stories Transforms Our Lives, pgs. 57-61

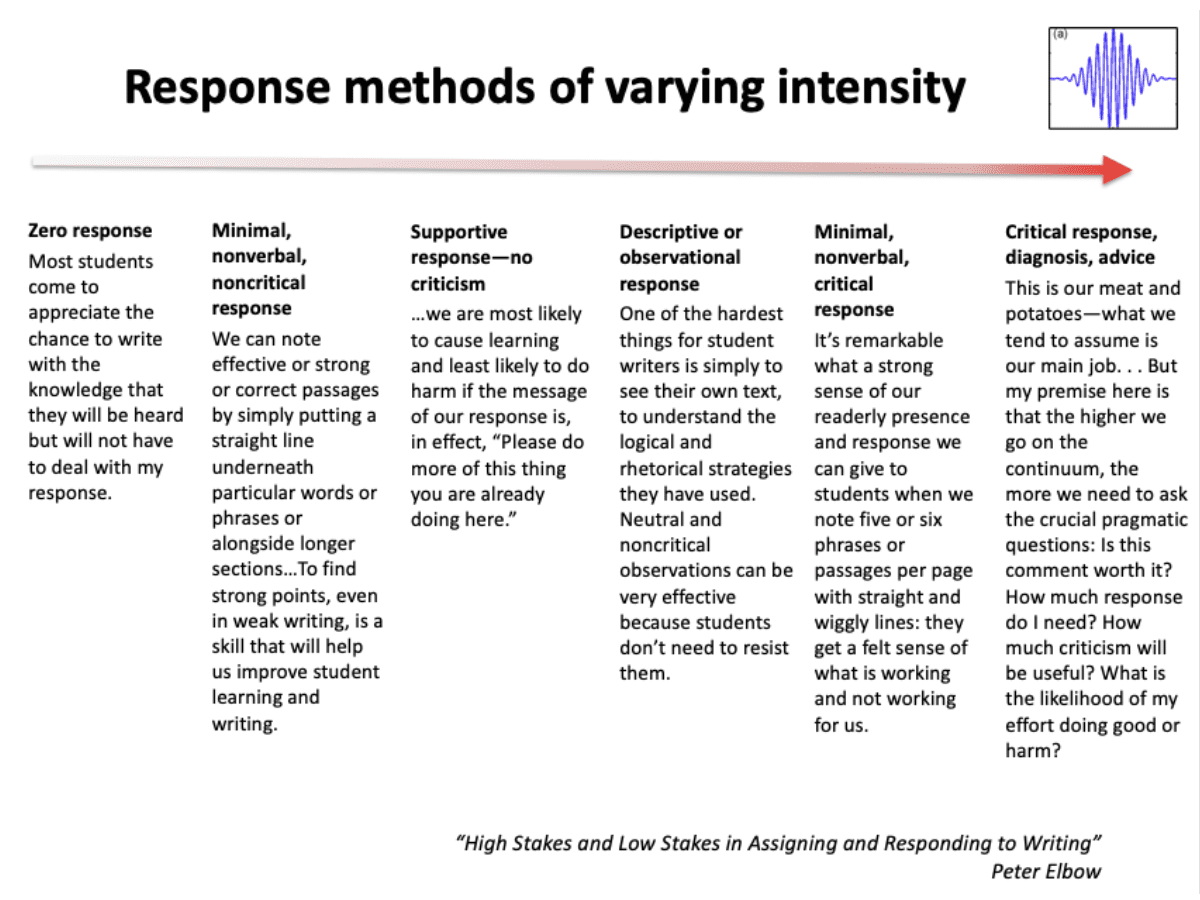

2. Intensity of response. Rather than having readers give you critical response or diagnosis, readers might offer supportive response to help you build on what you are already doing well.

While individuals find it therapeutic to write stories or narratives about their personal experiences related to COVID-19, other individuals find it helpful to learn more about the disease and its implications. Inquiry-based writing is a powerful way of harnessing the potential of research to answer the questions that most interest you.

This session will offer participants who want to process the implications of the pandemic through research. Activities in this session guide writers through the research process. These activities help writers refine the skills necessary to bring self-generated research inquiries into the public sphere, whether for education, awareness, or call to action. This session follows four steps:

- Identify what inquiry is and types of inquiry-based writing.

- Generate and evaluate inquiry questions.

- Find and evaluate scholarly and popular sources on COVID-19.

- Translate health/science information accurately and responsibly into an essay, report, or presentation.

- Reading: “The Color of Coronavirus: Covid-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S.,” Apm Research Lab Staff

- Reading: Michael Ollove and Christine Vestal, “COVID-19 Is Crushing Black Communities. Some States Are Paying Attention,” PEW

Like the first session on personal/narrative writing, inquiry-based writing starts with your values, your experiences, and your goals and interests, and that is what you will focus on in this module. This session will cover the basic considerations of inquiry-based writing, before we move into generating questions and drafting your own research inquires.

Inquiry is the process of asking questions to solve a problem. In education, inquiry-based learning is a way for students to generate research questions for further study and, thus, model the work of professional researchers. In this way, teachers become guides for students, rather than assigning research topics.

Inquiry-based writing instruction has been shown to provide more meaningful learning for students and keep students engaged. In inquiry-based writing, students can draw on personal connections in their writing and research (Eodice, Geller & Lerner, 2019; Geller, Eodice, & Lerner, 2016). When combined with clear expectations for writing and the opportunity for supportive feedback from a peer, such activities lead to deeper learning and personal development (Anderson et al., 2016).

Inquiry-based writing can be a potentially positive way to address trauma because it gets writers to focus on action. It is a way to build resilience.

- Reading: Louise Aronson, “Story as Evidence, Evidence as Story,” A Piece of My Mind

- Reading: “Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process,” National Library of Medicine

- Reading: Carl Zimmer, “How You Should Read Coronavirus Studies, or Any Science Paper,” The New York Times

Inquiry-based research is driven by the ongoing relationship between asking questions, seeking information, and refining the questions based on what you find. In this session, you will find resources and activities to help you frame your questions. From there, you can work on activities related to data gathering and data analysis.

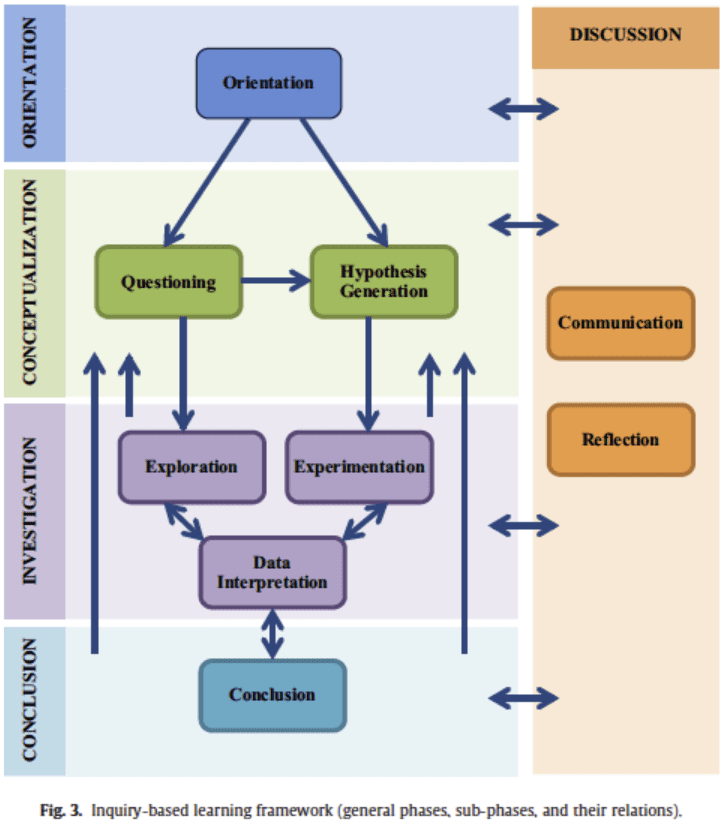

Inquiry-based research typically includes four phases: (1) orientation, (2) conceptualization, (3) investigation, and (4) conclusion. Discussion happens throughout the process

Session 2.2: Phase 1: Orientation

1. Orientation. Inquiry-based research starts with orienting yourself toward a topic. In other words, you want to find a topic to write about.

Orientation questions:

Using some of the COVID-19 healing narratives you composed in Module 1, or using your personal experiences living through the pandemic thus far, consider if there are potential research topics you can extract from these personal narratives.

- What are some COVID-19 topics that interest you?

- Why are you interested in those topics?

- Why are they relevant to your personal and/or professional experiences?

- What is your ultimate goal? Do you want to write an op-ed, give a public talk, write a research article, or something else?

At this early stage in the research process, we ask about your ultimate goal. That’s because no professional researcher waits until the end to think about writing. In fact, what we want to write often shapes how we go about conducting research, including how much research we do and what kinds of sources we use. For example, if we want to write an op-ed, we might only need 5-8 good sources. On the other hand, if we want to write a research article, we might need 20 or more sources.

Discussion: Often it is helpful at the beginning of a project to discuss your ideas with someone else. Talking to someone else can help you identify what really interests you. You can even brainstorm new ideas with a friend.

After orienting yourself to a topic, take a step back. When working on trauma-informed inquiry, we recommend some introspection before proceeding with your research. Professional researchers call the process of examining our own values, goals, and beliefs in relation to our research and teaching “reflexivity.”

Besides being helpful in understanding your values, goals, and beliefs in relation to your research, self-reflexive exercises can also help you think about the impact of your search on readers.

Self-reflexive questions:

- Why do I find this topic personally interesting?

- How does my identity impact my research interest and the ways I might answer my research questions?

- What potential harm might I do to myself by conducting this research? Are there triggers that I should consider before starting?

- What do I hope will come of my research? What will I do if I do not get the response that I hope for?

- Who might be helped by my research? Who might be harmed by my research?

Who do I want to read my research? Why them? What do I hope will be their reaction?

Session 2.2: Phase 2: Conceptualization

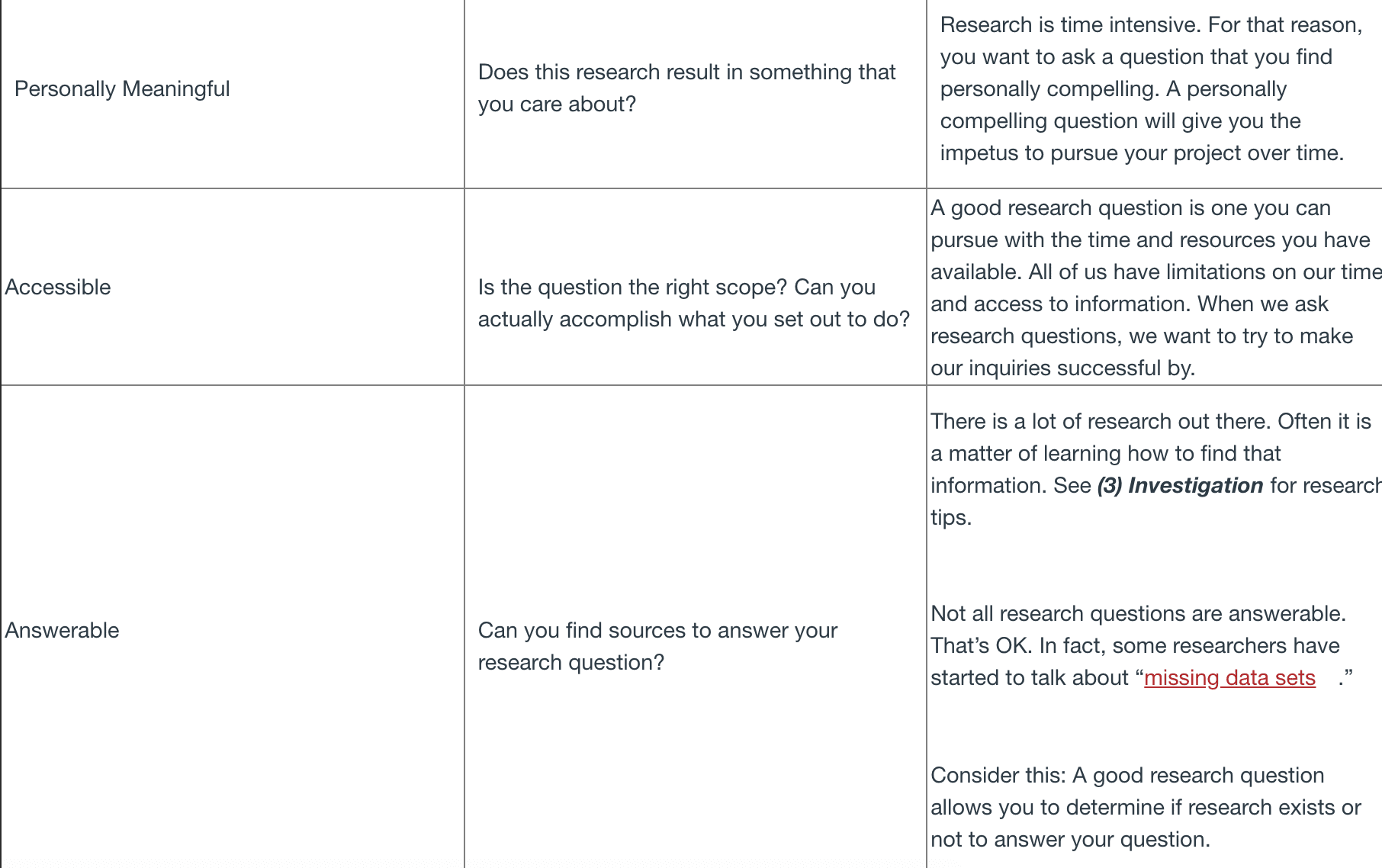

Conceptualization. Conceptualization is a complicated way of saying “asking questions” and generating some ideas (or hypotheses) about what you might find through your research. The trick to making inquiry-based research “good” is in asking good questions. A good research question is personally meaningful, accessible, and answerable.

Asking questions activities

Using the research topics you generated in (1) Orientation, begin to generate some research questions.

When you begin to generate research questions, don’t worry about good grammar or logic. Instead, try to think of as many questions as you can. Here are some to get you started:

- What topic is it that you want to learn?

- What is known about this topic?

- Who does this topic affect?

- What are some of the issues of conflict surrounding this topic?

- What are some aspects of your topic that are unknown right now?

- What might be some outcomes or uses of your inquiry?

- Using the fake news/fact-checking sites and the resources on how to find scholarly sources, briefly, how is the topic being discussed in popular and academic circles right now?

After you generate a list of potential research questions, ask yourself:

- How passionate do I feel about this topic? Who am I accountable to in doing this research? Am I doing this research for myself or someone else?

- Can I narrow my topic by age, time, geography, or some other way? What keywords are central to my research? For example, can I change generic words like “people” to specific words like “infants” or “senior citizens”?

- What sources might I be interested in reviewing to answer my question? What do I expect to find?

With the questions above as a frame, write a brief paragraph in which you narrow the focus and specify your inquiry issue/topic.

Session 2.2: Phase 3: Investigation

(3) Investigation. Now that you have a working research question, it’s time to start finding research. Adding research to your writing is a way to provide more context for your discussion and build your ethos as a writer. And it’s a great way to learn. “Sources” can include everything from newspapers and online forums to peer-reviewed scientific articles. Academic research, such as scientific articles, are published in “journals,” such as The New England Journal of Medicine

Collecting Sources

While a Google search will certainly generate a lot of information, it may not be the best information to answer your research question. Google searches take you to all kinds of websites, ranging from reputable research sources to idiosyncratic blogs. Google Scholar is a bit better but can often produce results that are difficult to filter and sort. Professional researchers use academic databases to locate “peer-reviewed” research.

The Northeastern University librarians have put together a video series on how to find academic sources. For example, in this series, they discuss how to use a search engine called Scholar OneSearch to find academic research articles. In this series, they explain how to improve your search strategies and find ebooks.

Beyond academic sources, government sources are really valuable in finding public health information (Note: government websites always end in .gov). In fact, many professional researchers regularly use websites like the Centers for Disease Control website to find information about disease rates. In addition to federal websites, states often have local information available on their websites. For example, this website has Massachusetts-specific information

Before the COVID19 pandemic, many academic articles were behind a “firewall,” meaning you had to pay to get access to the article. However, many academic journals have now provided free access to COVID-19 research in an attempt to help the public learn more about the disease.

Analyzing sources. How do you know whether a source is reliable or not? In general, academic sources are better than non-academic sources when you are conducting research. Professional researchers evaluate the quality of sources by looking at a few key markers:

- Type of source

- Author expertise

- Publication date

- Publication venue

- Research quality

The Northeastern library has excellent guides on how to evaluate sources, including data and statistics

Fake News and Fact-Checking Covid Sites

You can find a lot of incorrect information on COVID-19 on the internet. Below are some resources to help assess your sources.

Fake or Real? How to Self-Check the News and Get the Facts

False, Misleading, Clickbait-y, and/or Satirical “News” Sources

How To Avoid Misinformation About Covid-19

Poynter International Covid-19 Fact Checking Site

Investigation activities:

Now that you have collected some sources on your topic, it’s time to review them critically before writing up your research. What kinds of sources has your search yielded? What information is provided in those sources? What information do you still need?

For each source, ask the following questions:

- What is this source–for example, a blog, scientific study, op-ed, or government report? Is it relevant? What genre is it? Is this source based on opinion or facts?

- Who is the author? What expertise do they possess?

- When was the article published? Does it contain timely information?

- Where was the source published? Is that a reputable journal or impartial news source? If it is a scholarly source, does the journal have an impact factor–that is, an indicator that other researchers cite research from the journal? Has the article been cited? Was it peer reviewed?

- How was the research conducted? Where was the research conducted?

After reflecting on the results of your research and what that research has yielded, you may decide to go back and do some more research. Try finding new sources if you cannot answer the questions above. Also, it’s not uncommon to find gaps in your research at this stage. You may need to go do more research, if you haven’t found exactly what you need to answer your research question.

- Question to Consider:

At this point in a research project, it’s very helpful to talk to someone about your research. By explaining what you are researching and what you have found, you are synthesizing your research findings into chunks of information. That chunking will help you both process what you have learned and help you consider what else you might want to know.

Session 2.2: Phase 4: Conclusion

(4) Conclusion. After you have found and analyzed sources to answer your research question, you need to figure out what to say. Professional researchers sometimes call this a “story,” and many professional researchers talk about the “story” of their research. A good research project reads like a story–there is a question, a search for answers, and …. ANSWERS!

So, how do you tell a good story with all the information you have found?

One way is to use a storyboard. There is no one right way to make a storyboard. It can be as simple as bullet points, a traditional outline, or a series of images. A storyboard or outline also helps you figure out where you need research in your story. After all, no one wants to read a series of research summaries. Readers want a presentation, essay, or report that is punctuated with research findings.

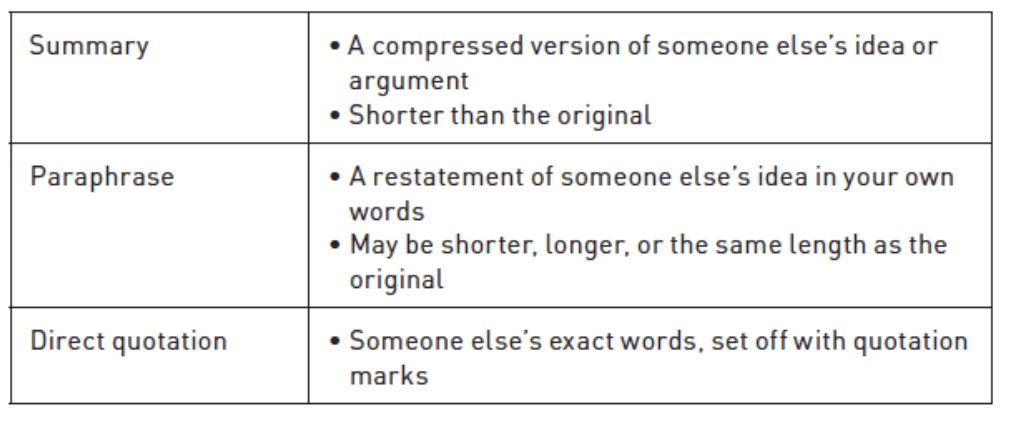

Once you figure out where you want to add research in your presentation, essay, or report, you need to decide how you will use that research. There are three main ways that writers include research: summary, paraphrase, and direct quotation.

How to Summarize

Summarizing involves a specific process of converting what you have read into a much shorter version. The process can generally be handled in four steps:

- Identify the main claim and write it in your own words. Often, you will find it easiest to write this if you read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion of an article. The main claim is usually most developed in these sections. If someone were to ask you, “What is this about?” this statement would be your answer.

- Explain the main arguments that support this claim. You can omit aspects that are not central to supporting the claim, such as specific details or examples.

- Include necessary context. Sometimes a small amount of context, such as the circumstances of the research, can be helpful to understanding the claim or conclusions.

- Avoid personal opinion or interpretation of the original. This point holds true for students working on summary assignments for school but may be “bent” in professional writing, depending on the purpose and audience. (Irish, 2015, p. 209-210)

Make sure that if you are summarizing, paraphrasing, or quoting someone else’s ideas or words that you cite your source. Usually a citation includes an in-text reference and an entry in a References page. The Northeastern University guide to citing sources is a good resource for learning the different ways of using sources.

Conclusion activities:

Now that you have found good sources that help you answer your research question, it’s useful to take a step back before writing up your findings. At this moment, you are “close” to your work, which means that you may not see gaps or strengths in your research process. Talking to a friend can help you get some perspective. The following questions can also help you self-assess your work:

- What are the main themes, ideas, or findings that I find most compelling from my research?

- What assertions can I support with the sources I have found? Do multiple sources support those assertions?

- Have I answered my research question? If not, do I need to change my original research question?

- How do I feel about this research? Have I learned something? How has that new knowledge changed me?

- What might happen based on my research? What might be a positive effect? A negative effect?

In this session, you will take the results of your initial inquiry activities and research analysis from the first two sessions and produce a piece of accessible research writing.

Now that you know how to ask a research question, conduct research, and analyze your findings such that you can make a storyboard or outline, it’s time to finish drafting your presentation, report, or essay.

While many writers compose narratives chronologically, research writers tend to compose their texts in chunks. They might write a short introduction to frame the main idea of their report or presentation, but then move to the center of the report or presentation to work on a key idea. By using a storyboard or outline, you can easily move around in your report or essay to different sections and not lose the overall coherence of your work. This nonlinear composing process also helps with fatigue when working with complex research.

Getting feedback on your inquiry-based writing:

While inquiry-based writing can take many forms, there are some key elements in all research writing. So, while you may or may not have a friend who can evaluate the technical content of your inquiry-based writing, you can still have a friend give you some feedback on the following:

- What is the research question?

- Why is that an interesting research question? If you can’t tell, offer some suggestions.

- What data did the writer collect to answer that question(s)?

- Do you feel that the writer has enough data to answer their research question? Why or why not? Do you feel that the researcher has the right kind of data to answer their research question? Why or why not?

- What is the biggest surprise in the findings? What seems to be the most important finding?

- What remains unclear to you after reading the draft?

Session overview: Now that you have a firm grounding in your self-generated research projects, the community entry point activities that follow in this module help you position yourselves within larger community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Community-based prompts are for writers who want to advocate for a particular position and work with members of their own communities. These activities also provide a foundation for the skills, such as interviewing.

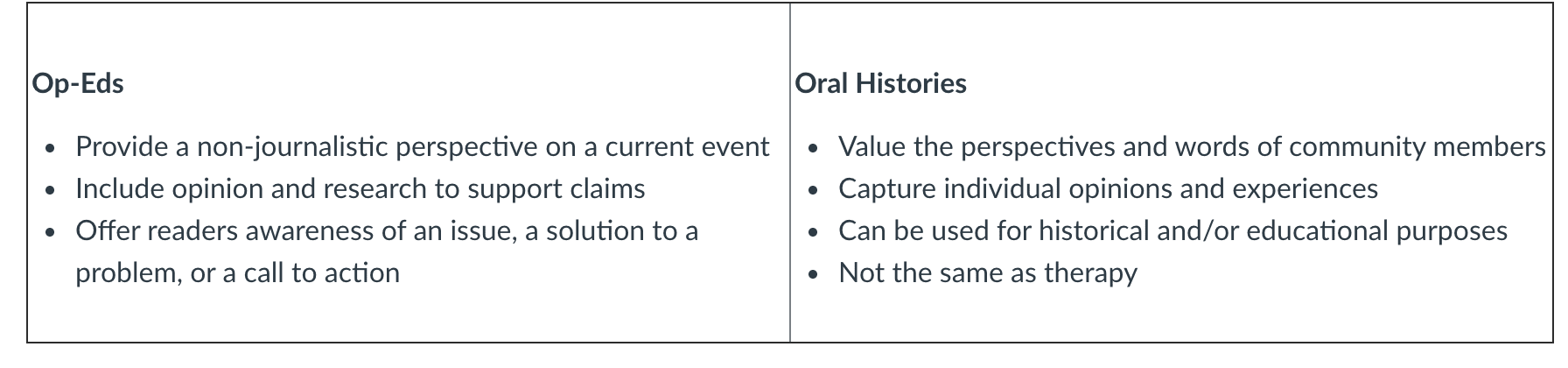

In this session, we offer participants two ways of using writing for community-based projects: op-eds and oral histories. Op-ed advice is targeted for participants who want to take their self-generated research inquiries and use their findings as means to advocate for particular positions, interventions, or recommendations. Oral history advice is for participants who want a more intimate way of using writing to advocate for community awareness by capturing the stories of community members. Activities in this session guide writers through the writing process for both of these activities. This session follows three steps:

- Identify common types of community-based writing.

- Generate op-ed pitches and trauma-informed interview questions to support public-facing narratives and oral histories.

- Draft an op-ed or transcribe an oral history interview.

- Reading: Tasha Golden, “Where Your Writing Can Go: Storytelling as Advocacy,” The Ploughshares Blog

Community-based writing values the perspectives of individuals outside the academy. That means, community members’ ideas guide the research and final product. For example, op-eds are often meant to give voice to individuals who are not professional journalists but who may have particular expertise in a topic or lived experiences that offer readers valuable perspectives. Other community-based writing projects, such as oral history projects, are meant to document people in specific locations at specific times in history.

In this session, you will gain exposure to these common types of community-based writing, including strategies for developing your ideas as well as reading published examples.

- Reading: Reann Gibson, “Communities of Color Hit Hardest by Heat Waves,” The Boston Globe

- Reading: David Lat, “Op-Ed: People ask me if I’ve recovered from COVID-19. That’s not an Easy Question to Answer,” Los Angeles Times

- Sabrina Strings, “It’s Not Obesity. It’s Slavery,” The New York Times

- Reading: “Writing OpEds That Make A Difference,” Indivisible

- Reading: Kristine Maloney, “Op-ed Writing Tips to Consider During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Inside Higher Ed

- The Op-Ed Project, “Op-Ed Writing Tips and Tricks”

- Reading: “Covid-19 Oral History Plague,” Journal of the Plague Year

- Reading: Jo Healey, “Reporting on Coronavirus: Handling Sensitive Remote Interviews,” Dart Center

- Reading: Jina Moore, “Covering Trauma, A Training Guide”

- Reading: Jina Moore, “Five Ideas on Meaningful Consent in Trauma Journalism”

- Video: Trauma-Informed Interviewing: Techniques from a Clinician’s Toolkit

In this session, you will apply the strategies from the previous section to your own writing process, clarifying your stance and audience through drafting a pitch for op-ed projects and generating interview questions for oral histories and similar narrative projects.

Use the following questions to help draft your brief pitch and begin framing your draft:

Preparing for the Op-Ed

1. Why write an op-ed? Clarify your purpose:

a. Inform (make aware of)

b. Educate (going a little deeper)

c. Persuade

d. Inspire

e. Advocate/offer call to action

f. Relate

2. Basic questions to draft a pitch:

a. What’s your issue? What is the “hook” or current event that frames this piece?

b. Why right now?

c. What’s your unique perspective/recommendation within this issue? What is the counter view to this?

d. Why should you be the one to write it? (credentials, relevant life experiences, etc.)

e. Where should you pitch it? (local or national publication)

3. The argument: How are you making your case?

a. Anecdotal evidence–the personal, contextual details that engage the reader (potentially from Module 1)

b. Research–the evidence to support your recommendation or position (from Module 2)

c. Testimony–the words of others to help you make your case (from oral histories)

4. The writing:

a. Be as concise as possible (typically around 750 words)

b. Use active voice

c. Avoid clichés

d. Use specific examples

e. Have a consistent voice

f. Know your audience

Preparing to interview community members for oral histories

1. What are the goals and purpose for collecting these oral histories?

a. “To provide a historic record of what has happened and its multiple impact on individuals and within communities.

b. To share the results of these findings with professionals who make humanitarian interventions in the aftermath, and to record the success and failures of those programs if resources permit.

c. To support those who give testimony in creating narratives that through their very expressivity and creativity can help rebuild communities and reconstruct identity in the wake of the catastrophe.” (Albarelli et al., 2020, p. 13)

2. Define the frame of the project:

a. Place. Currently, most interviews should be conducted remotely.

b. Time. You must decide if you will interview someone while an event is happening, immediately after an event, or after some period of time has passed since the event.

c. People. The people you interview are called “narrators.”

d. Technology. Decide what technology you will use to conduct the interview.

e. Legal issues. Read the claim rights, if you are using professional software for interviewing.

3. Select the focus of the interviews:

a. Will you focus on a specific moment in time or an expanse of time?

b. Will you use the same questions for each narrator, same themes but varied questions, or freeform format?

c. How long will you interview a narrator?

d. Will you be seeking a second interview?

e. Will you give narrators the opportunity to listen to their interviews?

4. Develop a plan for listening and publishing interviews

a. How will you listen for accuracy of meaning?

b. How will you address awkward passages or inaudible passages in the interviews? Will you remove filler words like “uh” and “um” from the transcripts?

c. Will you trace themes across interviews and provide an analysis or build compelling profiles of individual narrators?

d. Will you select the most interesting quotes or allow the interview to be published in its entirety?

e. What will you do about interviews that did not go well?

f. How will you understand the way your perspectives might shape how you interpret the interview?

g. How might the interviews be used for unintended purposes? How might you safeguard against that happening?

5. Develop a plan for storing the interview files

a. Who owns the rights to the interviews?

b. Where can the audio or video files be stored safely so as to ensure the confidentiality of you and the narrators?

c. If you need to access the audio or video files in the future, can you do that easily?

d. If you plan on destroying unused material, how can you ensure that the information has actually been destroyed or erased?

Interviewing Community Members: Interviewing Tips

Interviewing community members who have undergone traumatic experiences requires patience, empathy, and resilience. Interviewing requires that we become witnesses to events. When those events are catastrophic or traumatic events, then we are emotionally and physically implicated in those events. Moreover, because of the difficult nature of interviewing community members who have undergone traumatic experiences, it is critical to set-out the framework for your interview before you begin asking questions.

When contacting potential community members:

- Explain the purpose of the interview and ensure that you explain the interview is voluntary. You may never coerce someone into an interview.

- Explain how the interview will happen–for example, do you plan on recording the interview? Respect narrators wishes if they do not want to be recorded or videotaped. All narrators may stop an interview at any time, if they wish.

- Explain who you are. (See self-reflexivity in Module 2)

- Explain how the interview material will be used. Will the interview be made public or kept private?

- Explain how you will ensure the safety and privacy of participants being interviewed. Will narrators’ real names be used or will they be given pseudonyms?

- Confirm the day, time, length, and format of the interview in advance.

- Explain any compensation or other benefits from the interview.

- Provide your contact information.

Good oral history interviewers (Adapted from Aras et al., p. 15):

- Rely on respectful language and acknowledge the pain that narrators may have suffered. Acknowledge grief but do not use phrases like, “I know how you feel.” Such phrases can seem like trivializing other people’s pain.

- Use warm-up questions to make narrators feel comfortable at the beginning of the interview. A warm-up question, such as asking narrators for their preferred names and pronouns, shows narrators that you are willing to allow them to shape the interview content.

- Allow narrators to answer questions in the ways that feel most comfortable to them. Open-ended questions–questions with no right or wrong answers–are best.

- Base questions on what narrators have already said. This allows interviewers to continue the conversation across multiple questions. For example, ask about a similar incident or ask narrators for their assessment of an event. You can also prompt additional information simply by asking, “Could you tell me more?”

- Allow narrators time if they need to cry or take a break.

- Summarize and confirm what narrators have said through a technique called “sayback.” When using sayback, the interviewer says something like, “So, as I hear you saying……” This technique allows the narrator to correct a faulty misinterpretation on the part of the interviewer.

- Allow narrators to describe events, expectations, and emotions in their own terms. Do not correct narrators.

- Use objects and texts, such as dairies, to help prompt insights from narrators. If you wish to use such materials, you should always invite participants before the interview to bring such items to the interview.

- At the end of an interview, a good interviewer also thanks narrators and asks them for any information that they might wish to share. If an interviewer is worried about a narrator, they might follow-up with a call to check on them.

Listening to Trauma

In the 1960s, the CUNY system developed a program called SEEK to expand university admissions. Notice in this interview with Marvina White how the interviewer listens and respects Marvina’s recounting of trauma. And in this inquiry-based article, notice how Sean Molloy, the interviewer, retains that same respect.

Important characteristics of an interviewer are:

- Attention: “This is primarily conveyed through questions that often include a phrase or thought of the narrator at the beginning, and often an atmosphere of silence that is filled with expectation and interest.”

- Connection: “The ability to create an environment of neutral and supportive listening in which any experience, no matter how graphic or harrowing, can be conveyed and absorbed, without resulting in creating excess emotion within the fieldwork situation.”

Constructive listening and interpretation: “The activity of listening, usually silently, must be punctuated by the activity of intelligent questions which crystallize the connections made, most importantly, by the narrator but also by an attentive oral historian who can reflect additional connections and encourage the process of interpretation.” (Albarelli et al., 2020, p. 26-27)

- Question to Consider:

- At this point, you will want to draft some interview questions and ask a friend to help you think through possible answers. Often you will find that you have too many questions! For an oral history, it is better to let narrators spend time working through a story or a few stories, rather than briefly answering a number of questions.

- Interviewing Activity: Using the interview tips, identify two people whom you would like to interview. Interview each person for 30-45 minutes.

In this session, you will expand your op-ed pitch or your interview questions and compose a full draft of your community project. This is where the personal narrative exploration you did in Session 1, the research and analysis you worked on in Session 2, and the scaffolded activities you did in the first two sessions of Session 3 come together to support a community-based COVID-19 project.

Op-ed: Using the writing tips and strategies in Session 3.2, write an approximately 750-word op-ed that includes a news hook for your reader, a clear position and counter position, and specific anecdotal and research-based evidence to both engage the reader and support that position. Remember that you are likely writing about a community issue for a public audience, so accessible, clear language and attention to your specific intended audience–local newspaper? National media outlet?–are important. Individual publications most often offer specific submission guidance on whether they want pitched ideas or full drafts, but in either case, it is best to have a full draft prepared in case an editor responds with interest.

Oral history: After the interview, listen to the interview again and try to transcribe the audio as accurately as possible. If you do not have time to transcribe the entire interview, try transcribing pieces of the interview that you find most compelling. If you find the audio too fuzzy at times, you can add ellipses to the interview transcript to note that the audio was inaudible. For example, “I called my mother at the nursing home to see …[inaudible]… The nurse told me that my mom had been transferred to another room.”

Getting feedback on your community-based writing

Op-ed: Before you send your op-ed out for possible publication, you will likely want some feedback. Consider your intended audience. Remember that you can write for local community outlets as well as more general publications, and see how your writing resonates with an intended reader or readers. Some feedback that may be helpful include questions like these: Are the argument and counter argument clear and easy for readers to pinpoint? Does the reader feel connected to the topic through anecdotal experiences? Is the argument supported with facts? Is the scope of the research and content working, or do your readers need more details to arrive at your point with you?

Oral history: While it is always most ethical to allow narrators to review interview transcripts before those transcripts are made public, you need to set expectations. Interviews are not polished speeches. What makes an interview powerful is the rhythm of everyday language, the persona of the speaker, and the bond with the interviewer. So, while it is fine to allow narrators to correct factually incorrect information and revisit passages that need further elaboration, you want to avoid revising the interview transcript into a speech. You also will want to allow narrators to delete any information they feel puts them at risk. Sensitive comments that are made based on trauma are fine; comments that jeopardize the well-being of narrators or others named in the interview are not.