By Jonathan D. Fitzgerald

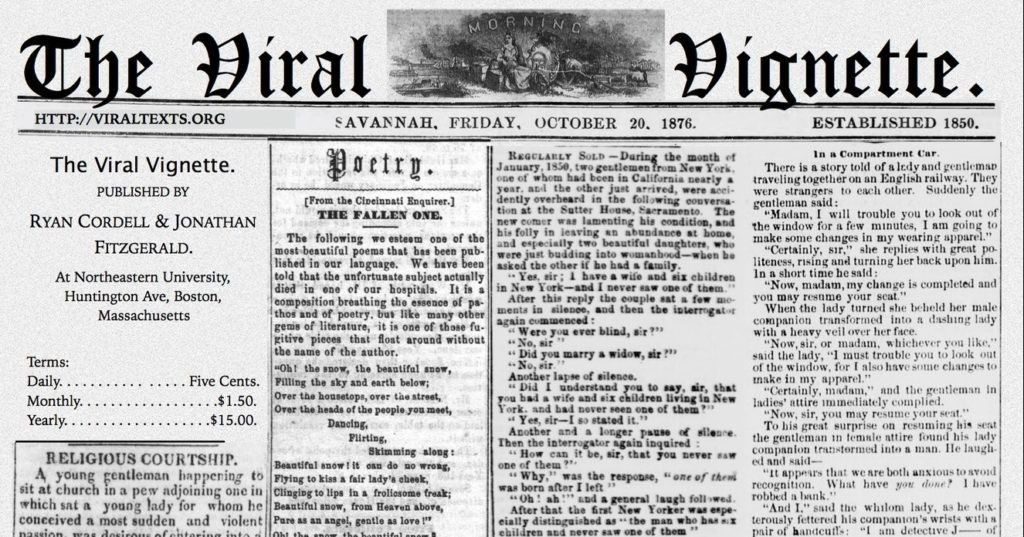

The following is a companion piece to a paper that Ryan Cordell and I presented at the ALA 2016 Symposium, The American Short Story: An Expansion of the Genre. Our paper is titled “Vignettes: Micro-Fictions in the Nineteenth Century Newspaper” and in it we discuss the vignette as an essential genre in antebellum American letters, both influential in the development of sentimental fiction and a precursor to the prose writing later styled “literary journalism.” For this presentation, I was a grateful recipient of a NULab Travel Grant.

We entered into this project with the notion of vignette as hybrid genre and much of my effort to classify genre within our corpus has been an attempt to bring to the surface some of these harder-to-classify genres. In an effort, then, to consider the hybrid nature of the vignette, I’ve been attempting to use computational classification methods to place it on a spectrum between news and fiction.

I began with three sets of texts—news items culled from our corpus of reprinted nineteenth-century newspapers and identified via my classification model, vignettes also derived from that corpus but identified by manually reading a subset of the larger data set, and fictional short stories, which were derived from the Wright American Fiction project out of Indiana University. It was important for us to identify shorter works of fiction from the Wright corpus as we had the sense that vignettes bear a closer resemblance to nineteenth-century short stories rather than novels. Thus, from the full set of fiction in the Wright corpus, I manually selected the 200 shortest pieces as indicated by file size. But, even then, the short stories are substantially longer than most news pieces from the Viral Texts corpus, which, in turn are longer than the typical vignette.

In an effort to ensure that the length of the text wasn’t skewing the results unnecessarily, I needed to do some preprocessing on the Wright texts. I started by removing the metadata about the texts that is included in each file derived from the Wright corpus. This includes information like title, author, publisher, etc. Then, I removed all line breaks so that the text would read as a continuous string. from there I sampled down each text to a random selection of 2000 consecutive characters. The logic behind this was that 200 texts of 2000 characters each would create a corpus that is about equal in size to the corpus of news items from the Viral Texts data. Then, I sampled 200 news items from a larger corpus of over 800 texts. Finally, I combined the fiction and news corpora with the 198 vignettes that I had manually identified.

The classification method that I’ve been working with uses topics derived from topic modeling a corpus as tokens, as opposed to words, which are more commonly used. The reasons for this are many (I discuss this at greater length in this post), but particularly we’ve found that decreasing the dimensionality in this way leads to a more accurate classifier and, importantly, makes it easier for a human researcher to understand the computer’s logic. I experimented with different numbers of topics to find a number that would be best suited for classifying texts in my corpus of roughly 600 texts and 50 topics seemed to be the magic number.

I then use these 50 topics to train the model on what constitutes fiction and what constitutes news. Here are some of the topics:

- states united sthe government state

- people public made power great

- york ohio texas ram rammy

- year total 18 amount fiscal

- war secretary letter general command

- lord prayer ou thanksgiving brudder

- man time good young long

- life heart room night side

- father wife home mother poor

- thy thee lay body thou

- frank circumstances determined harrington henry

- farmer pay bill aud merchant

If you’re not familiar with topic modeling, the first thing you’ll notice is that these topics are not actually topics in the way you might conceive of that word. That is, it’s not as if these topics tell us what the texts are about. Rather, in topic modeling, topics are groupings of words that are commonly found in close proximity to each other. In fact, the topics you see here are not the full topics, rather they represent the first five words of each topic.

In my corpus, I identify the genres of news and fiction, but label the vignettes as “unknown” since we ultimately want the classifier to identify these as either fiction or news. That is, we’re not telling the computer that we know that the vignettes are vignettes and asking it to tell us what it thinks they might be. So, when the unknown (vignettes) are removed and a model is created, we find that the classifier is very accurate. It can accurately identify news items and fictional pieces around 90% of the time. This is a check to be sure that the classifier is working the way it is supposed to, and once we see that it is, we can introduce the vignettes as unknowns and let the computer classify these. While the numbers can vary, the classifier most often splits the vignettes between news and fiction within a range of 35/65 and 50/50. That is vignettes are most often misclassified as news, but only just barely. In the majority of my experiments, the split is close to even.

What we see then, is that a computational classifier that is highly accurate at determining the difference between news and fiction based on topics derived from topic modeling, finds that vignettes are indeed a hybrid of news and fiction. We have run this experiment using a classifier that is seeded with words instead of topics, and found similar results, though the classifier based on words is not as accurate at determining the difference between news and fiction. And, interestingly, the classifier trained with words most often mistakes the vignette for fiction, as opposed to news. This is kind of cool, and I have to look into it more.

In an effort to ensure that what we are seeing is not just a random sorting of an unknown genre into two known genres, I repeated the experiment using advertisements and poetry derived from the Viral Texts corpus instead of vignettes. Indeed, in these cases the classifier was also effective at guessing what each genre—poetry and ads—was most similar to. That is, poetry is classified as fiction around 80% of the time, and advertisements are classified as news items around 60% to 70% of the time. This last finding might be surprising if you’ve never encountered an advertisement in a nineteenth-century newspaper; they are quite prosaic. In fact, they often read similarly to vignettes, which explains why the classifier aligns them more closely with news items.

We are firm believers in the value of combining the skills of distant reading, which I’ve been describing here, with our more traditional and disciplinary practice of close reading, and so the next step in our process was to read the data created by the classifier to determine if we could discern what exactly makes the computer identify some vignettes as news and others fiction. We can do this first by skimming what you might call our appendix—that is, the topics and their alignments as either fiction or news. When we do this, we find, unsurprisingly, that those topics that include more domestic words like young, good, heart, room, home, mother, and farmer align more closely with fiction. On the other hand, topics that include words like united, states, government, public, fiscal, and war align more closely with news. Vignettes, we’ve found, cover a range of topics and thus can be (mis)classified as either fiction or news.

From there, however, we need to dive into the texts themselves and read them more closely in an effort to understand what might make the computer classify them as news or fiction. This is a process that, as of this writing, is ongoing.

This post was originally published at http://jonathandfitzgerald.com/blog/2016/10/10/the-viral-vignette.html