By Julianna Wessels, NULab Fellow and English PhD Student

See here for the project’s Storymap

Background Information

Born out of the efforts of digitizing, clipping and researching geographical locations mentioned in fugitive slaves ads from the Barbados Mercury Gazette (1762–1848), the Fugitive Barbados Mapping Project utilizes speculative knowledge to capture movement in the archive. As stated by author Saidiya Hartman in her essay “Venus in Two Acts,” “The intention here isn’t anything as miraculous as recovering the lives of the enslaved or redeeming the dead, but rather laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible. This double gesture can be described as straining against the limits of the archive to write a cultural history of the captive, and, at the same time, enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration” (11). With this framework in mind, I was able to research the origin and speculated destination locations of fugitives mentioned in the Barbados Mercury via information provided by the Digital Library of the Caribbean and the Legacies of British Slave-ownership Project at UCL. The Fugitive Barbados Mapping Project aims to place the paths of individual fugitives together on a map to allow for journeys to be put into conversation with one another and for potentially new insights and patterns to be drawn.

The first crucial step for this project to come to fruition, long before its conception, took place in 2018, when the Barbados Mercury and Bridgetown Gazette was digitized at the Barbados National Archives. The project of digitizing and preserving this important primary source was headed by Lisa Paul, Brock University; Ingrid Thompson, director of the Barbados National Archives; and Amalia S. Levi, Independent Archivist. The project was funded through an Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) grant from the British Library. Covering the time period from 1783 to 1848, this primary source provides insight into life in this British colony in the Caribbean during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Given that many other primary sources, such as plantation records or government records have been lost or destroyed, the Mercury stands as a particularly useful source in representing the slave society and economy that existed on the island, albeit from a deeply colonial perspective. The period that the Mercury covers includes a tumultuous time in Barbados given that a slave rebellion led by African-born enslaved leader Bussa occurred in 1816 which, in turn, sparked a series of rebellions in the West Indies, ultimately leading to the abolition of slavery in British colonies in 1834.

In March 2019, the Barbados National Archives and the Early Caribbean Digital Archive at Northeastern University partnered to create the Barbados Runaway Slaves Digital Collection project. At public workshops, participants worked to extract runaway ads from the pdf digital versions of the Mercury, to transcribe the text of the ads, and to enrich the human stories in each ad with additional contextual information. The initial founders of the Mercury archiving project have expressed great interest in having students and professionals utilize the information contained in the Mercury as the basis for digital humanities projects.

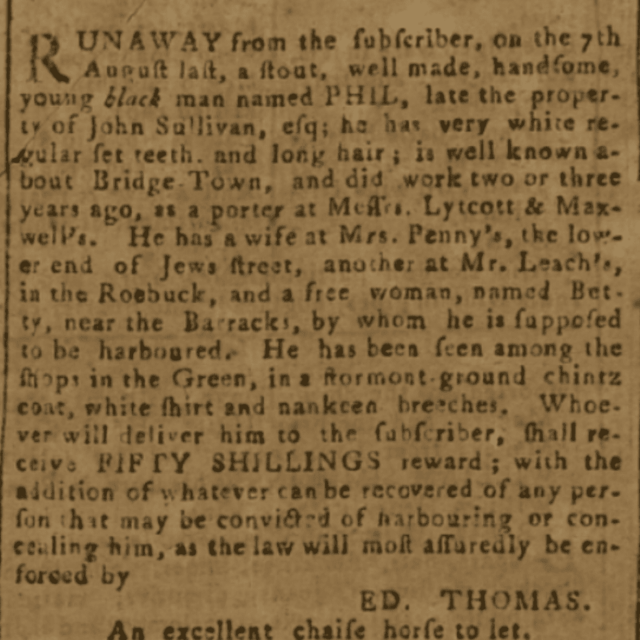

Runaway ads appear regularly throughout the newspaper and provide information on the location and description of fugitives who have escaped bondage and are being sought by their enslavers. Offering reward money for capturing fugitives and enumerating the locations where the fugitives have last been seen or are expected to seek refuge, these ads tell the stories of the paths to freedom that fugitives took in Barbados during colonial rule.

Methodology

In the construction of this mapping project, the questions of how maps would be displayed as well as which fugitive paths would be included on said maps were the most challenging. After sifting through a few hundred fugitive ad clippings in the ECDA database, I decided to initially start out by logging the data of every fugitive that I could accurately geographically locate with my given resources. Once I had data gathered for close to one hundred individual fugitives, I began to notice that a large number of ads either only listed an origin location and no destination location or vice versa. Additionally, some ads did not list origin or destination locations or would only ask for a fugitive to be brought to “The Cage” in Bridgetown, which refers to a literal cage where enslaved individuals would be held until their enslavers came to reclaim them. To best outline potential journeys that fugitives might have taken, I ultimately decided to only map the journeys of fugitives where I could accurately locate the latitude and longitude of both the origin and speculated destination of their journey.

A third challenging decision that I needed to make during the mapping of destinations for this project was in deciding which speculated destination to map for a given fugitive when multiple locations were listed. Some ads, for example, would list locations where a fugitive may recently have been spotted; where a fugitive’s mother, sibling, spouse or child was located; or where the last estate or plantation a fugitive previously worked at was located (in thinking that they may have returned to visit friends/family). Given such ads with multiple speculated destinations, I decided to log all speculated locations and to attempt to locate as many of these as possible. If I was only able to locate one location, this was the location that I decided to map for the speculated destination. If I was able to locate more than one speculated location, however, I would attempt to decipher which of these locations the ad stressed as most likely being the location where the fugitive was and mapped this location.

Finally, in considering which mapping platform to use, I selected ArcGIS due to the ability to form maps with multiple layers that utilized different representations of terrain. I also appreciated the ability to craft various mapping layers on ArcGIS and publish them to the ArcGIS story map platform where I could provide contextual information for my maps. I decided to create one layer of map with origin locations of fugitives, one layer of map with destination location information, and one mixed layer with alternating origin and destination locations for each fugitive. With these three mapping layers I was able to create one map displaying origin location, one displaying destination location, one sliding map with origin and destination locations, one mixed layer map with origin and destination locations connected with clear lines to show crossovers of fugitives speculated paths, and finally one map with mixed origin and destination locations to walk viewers through the journeys of each fugitive with the ad clipping included.

Map Information

Each of the five maps included on this Story Map project present the story of fugitive journeys in a distinct way. Considering the first map represented, the origin layer, this layer shows the starting location of each fugitive as listed in a given ad, with each symbol on the map representing an individual fugitive. By clicking on each location, more detailed information such as the name of the fugitive, estate name, and geographic coordinates of the location listed in each ad will appear. The second map is the destination layer, displaying the speculated location that each fugitive is thought to have journeyed to. As with the origin layer, users can gain more information on the name of the fugitive, estate name, and geographic coordinates of the location listed in each ad by clicking on the location. The third map displayed, the swipe map, presents the runaway path of each fugitive more visibly with the black symbols on the left side of the screen representing origin locations and the red symbols on the right of the screen representing speculated destination locations.

With each fugitive being represented by a different symbol, users are able to track the movement of a given fugitive more clearly. The fourth map displayed, created using ArcGIS Pro, connects the origin and destination locations of all fugitives mapped with the red dots representing origin locations and blue representing destination locations. The lines also utilize arrow markers at the end to more clearly display which direction a given fugitive was moving in. The goal behind this map was to visually display which fugitives might have crossed paths. Additionally, this map most clearly shows how the origins of some fugitives were the destinations of others and vice versa. In the fifth and final map displayed, the journey map, the origin and destination of each fugitive is laid out numerically with each fugitive’s origin and destination displayed sequentially to display the pathway taken. By scrolling through the locations, users can see the various pathways each fugitive took across the island as noted in the ads.

Reflection

Reflecting on what these maps make visible, each one of these maps attempts to depict the movement that a given fugitive might have made to connect with friends and family, or to potentially obtain freedom by journeying to the port in Bridgetown. As can be seen most clearly via the destination, swipe, line, and journey maps, a large number of fugitives did end up journeying to Bridgetown, the largest city and major port on the island. Although it remains unknown as to why these fugitives were traveling to Bridgetown, the movement to this area could indicate that fugitives were more easily able to hide in this area or perhaps were able to board ships to escape Barbados altogether. Unlike the more consistent South (origin) to North (destination) movement pattern depicted by U.S. Slavery freedom pathway mapping projects, this project displayed an overall lack of consistent directions, outside of the movement towards Bridgetown. All five maps of this project rely heavily on speculated information, given that destination locations were unknown, and when considered in tandem with the ads utilized in this project, attempt to provide a fuller image of where these individuals lived, who they might have interacted with and where they may have journeyed to, to escape the brutality of slavery.

This project, and the movement that it depicts, utilizes American writer Saidiya Hartman’s concept of “critical fabulation” in the way that its semi-nonfiction nature attempts to bring the suppressed voices of the past to the surface through the utilization of scattered facts, ads and speculated locations. These ads can be viewed in a semi-nonfiction light as the destination locations were geographic points, or areas, speculated by enslavers. Keeping this in mind, this mapping project certainly presents a tension between Hartman’s concept of critical fabulation, and particularly this concept’s desire to bring voices from the past to the surface, and the fact that all geographical coordinates for this project were speculated locations created by enslavers. As with any mapping or visualization project, in the process of selecting which ads I would map to tell the most clear and coherent story of fugitive movement on the island of Barbados, hundreds of other ads and stories were excluded from this narrative. I find it critical to acknowledge that the five maps created through this project tell the speculated stories of only forty fugitives, leaving the possibility for these maps to be expanded upon in future iterations.

In the end, I am humbled to have worked with such critical and fragile material. The difficult history of slavery on the Island of Barbados is, as stated by Kevin Farmer the deputy director of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, “one that underpins not only the history of this island but underpins the development of global capitalism for the past 500 years.” Although it can be easy to focus solely on platforms, spreadsheets and century old written text when crafting a mapping project such as this, at the core and the heart of this project lies the story of a group of humans who were suppressed by greed and attempting to relocate for a better life. The vast majority of these ads speculate fugitives to have run to familial ties on the small island of Barbados—whether to siblings, husbands, wives, or children—or to Bridgetown to potentially escape the island and obtain freedom. Each fugitive was a life, and each fugitive holds a story crucial to the history and creation of Barbados. In envisioning how these maps could be used in the future, I could imagine a future version of this map drawing connections between persons as well as locations. I also wonder if the visualization of the speculated paths taken by the fugitives mapped in this project could lead to fruitful familial lineage projects or if further information can be found in the future on fugitives who journeyed to the port in Bridgetown and potentially managed to obtain freedom. My hope, in the crafting of this project, is to restore the agency of enslaved individuals, to rejuvenate discussion surrounding these individuals’ lives and journeys and to potentially form new insights or connections by placing the paths of individual fugitives on a map with one another.

With a special thank you to Avery Blankenship, ECDA Project coordinator; Bahare Sanaie-Movahed, Senior Research Data Analyst at Northeastern University; Ryan Cordell, Associate Professor of English at Northeastern University; Nicole Aljoe, Associate Professor of English and Africana Studies at Northeastern University; Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, Distinguished Professor of English at Northeastern University; and Sarah Connell, Assistant Director for the NULab for Digital Humanities and Computational Social Science for all of your brilliant support and guidance with this project.

Sources Consulted:

Digital Library of the Caribbean. http://www.dloc.com . Accessed 10 April, 2021.

Hurdle, Jon. “Slavery Was Part of Barbados Life for Centuries. But Its History Can Be Hard to Find.” nytimes.com, The New York Times, Sept. 7, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/travel/barbados-slavery-history.html. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Levi, Amalia. “Digitization of The Barbados Mercury Gazette.” Web blog post. Endangered archives blog. British Library, 03 Aug. 2018. Web. 26 Nov. 2020.

Levi, Amalia S. & Inniss, Tara A. “Decolonizing the Archival Record about theEnslaved: Digitizing the Barbados Mercury Gazette.” Web blog post. A Journal of Caribbean Digital Praxis. Archipelagos, Jan. 2020. Web. 26 Nov. 2020

Legacies of British Slave -ownership. University College London, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/. Accessed 10 April, 2021.

“Remixing the Archive of the Fugitive Caribbean: Critical Fabulation as Decolonial Practice.” 9 April. 2021, Northeastern University, Boston. PowerPoint presentation