As a 2022–2023 NULab Graduate Fellow I partnered with NULab faculty Jessica Linker on an independent research project exploring nineteenth-century marriage manuals. This project, in part, began as an extended exploration into questions of materiality, digital textual modeling, the history of sexuality, and genre. As a graduate student at Northeastern, I have had the opportunity to work on many digital projects—including the Early Caribbean Digital Archive, Women Writers Project, Primary Source Cooperative, Early Black Boston Digital Almanac, and the Homosaurus. In my own research I am interested in the textual, structural, and conceptual relationships between modes of classification (and classification systems) and discursive texts about the body. Since I was first introduced to marriage manuals in nineteenth-century America by Avery Blankenship, this genre has been a central component of my scholarly interest, imagination, and now, dissertation. For this project I had two specific aims: first, identify digitized versions of marriage manuals and build a small test corpus; and second, apply computational text analysis methods to explore structural and conceptual textual features. For this project I specifically am using word embedding models, an process of modeling semantic meaning on mathematical models using natural language processing and machine learning. However, this is only the beginning of this research as I am further exploring the digital methods and research questions I outline in this post for my upcoming dissertation work.

Background: Marriage Manuals

Popular manuals or advice literature—or texts written and circulated for a general audience advising on moral, medical, scientific, reproductive, and social issues related to marriage and domestic life—have long existed as a popular genre. For example, the rise of literacy in the 1500s and 1600s in England corresponds with the rise and popularity of works for novice readers including popular medical books written for families rather than physicians and surgeons (Fissell 1–2). Such texts were widely circulated and often included in cheaper, printed formats like pamphlets and broadsides. Marriage manuals, broadly defined, cover not just medical information related to reproduction, childbirth and childrearing, or common illnesses, but also include information that a more modern audience might label as “sex education.” The history of didactic texts dedicated to the proper instruction of social and moral etiquette—as seen in Tabitha Kenlon’s work in Conduct Books and the History of the Ideal Woman—is an important historical and cultural backdrop to scholarship exploring gender and domesticity. Marriage manuals fit within the overlap between popular medical manuals and conduct books, often advising newlyweds or those entering the marriage market on how to look for and attract an “appropriate” spouse.

One text that saw widespread popularity and circulation over several centuries and across the Atlantic was Aristotle’s Masterpiece. First published in 1684 in England and “neither a masterpiece nor by Aristotle,” this text was a best-selling guide to pregnancy and childbirth that was reprinted numerous times in England and the United States (Fissel 3). When conducting research for this project, I found numerous copies of Aristotle’s Masterpiece across repositories with dates of publication well into the mid to late nineteenth century. Although Aristotle’s Masterpiece is only one example of popular texts about reproduction, it illustrates central issues about print culture in the nineteenth century that inform my understanding and questions about marriage manuals as a genre including the longevity in its consumption as a didactic text and it’s relationship to how authority is framed within it’s pages.

As projects like the Viral Texts Project (led by Ryan Cordell at University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana and David Smith at Northeastern University) have shown, printing in the eighteenth and nineteenth century was often a case of “borrowing” or reprinting and circulating previously printed materials. Before the creation of copyright law and regulations about plagiarism, entire volumes of popular texts were readily reprinted across different decades and geographical boundaries. Beyond trends in print culture during this time, I am interested in authorship in marriage manuals, especially as medical knowledge and practice became professionalized. The professionalization of such information as it is contained in popular texts is an important facet of my research: where do we see markers of professional expertise or authorship in marriage manuals and to what effect?

As the practice of medicine moved from domestic spheres to that of academic institutions, there are important changes in whose knowledge is prioritized, published, circulated, and consulted as expertise and what material and didactic forms within it are contained. Texts instructing women about domestic medicine like marriage manuals, as a genre, were being published and distributed at the same time of the professionalization of women’s medical education and training with the establishment of the New England Women’s Medical College in Boston (1850) and the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (1850). However, this is only one aspect of women in medical education and practice during the nineteenth century. The history of domestic medicine and women as healers outside of official educational institutions is a significant thread of current research on this topic, as Susan Brandt explores in Women Healers: Gender Authority, and Medicine in Early Philadelphia (2023). This project represents the first part of my research grappling with these research topics and intersections between and science, medicine, ideology in the classification of bodies and identities in didactic, domestic texts.

Corpus Building: Gender, Genre, Authorship, and Audience

A central endeavor of this research project was corpus building. For many forms of computational text analysis, corpus building represents a significant component of research design because how the materials in a corpus are divided, organized, or classified is directly related to the kinds of research questions or variables studied. For example, for research considering change over time, chronology is a significant facet that might be reflected in a corpus subdivided by specific time ranges. Or, a comparison between trends in language use between two different genres might best be studied in three corpora, a central “control” corpus and two corpora divided by genre difference. As I discovered and documented in a data preparation guide for my work with the Word Vectors for the Thoughtful Humanist Institutes for the Women Writers Project, corpus building is another iterative part of computational textual analysis.

With these guiding principles, I created my first corpus of popular marriage and sex education manuals using Gale Primary Source’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online: Women and Transnational Networks database, looking specifically for digitized materials with plain text versions (created through optical character recognition or OCR) easily available for download. Part of my decision to use this database was based solely on having easy access to fairly reliable plain text transcriptions of primary materials. When looking at marriage manuals with computational text analysis, I am interested in doing so at two different levels of scale: close reading marriage manuals as material objects and as distant reading with a large genre-based corpus. Creating a corpus of word embedding models requires plain text file formats which, for primary sources that have been digitized but not transcribed, requires the transformation of digital images into plain text files. While there is an entire subdiscipline of scholarship about different optical character recognition software and transcription methods regarding this process, transcription was well beyond the scope of this research project. Instead, I decided to create a “test” corpus based on my initial research interests and observations of marriage manuals as a proof of concept I would expand in further iterations in my dissertation work.

This initial marriage manual corpus contains OCR transcriptions of thirty print texts published between 1836 and 1910, largely in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. I identified titles of interest using a set of keywords: marriage hygiene, marriage hygiene manuals, sex education, sexology, and marriage manuals. In total this corpus is composed of over 2.7 million words and varies greatly in length with the largest text containing 269,000 words and the shortest only 3400 words. Looking only at the most frequent words across this corpus, two words easily stand out: women and woman. When assembling this corpus, I noticed two significant themes. First, many marriage manuals are highly gendered, either advertised or directly denoted in their titles for a specific audience by gender. Many titles easily exemplify this point: The Young Mother, or Management of Children in Regard to Health by William Andrus Allcott (1836), The Lady’s Companion: Or, Sketches of LIfe, Manners and Morals, at the Present Day (1844), The Young Woman’s Book of Health by William Andrus Alcott (1856), Women’s Love, and LIfe, A Book for Women and for Me by Jules Michelet (1881), and What Our Girls Ought to Know by Mary Studley (1878).

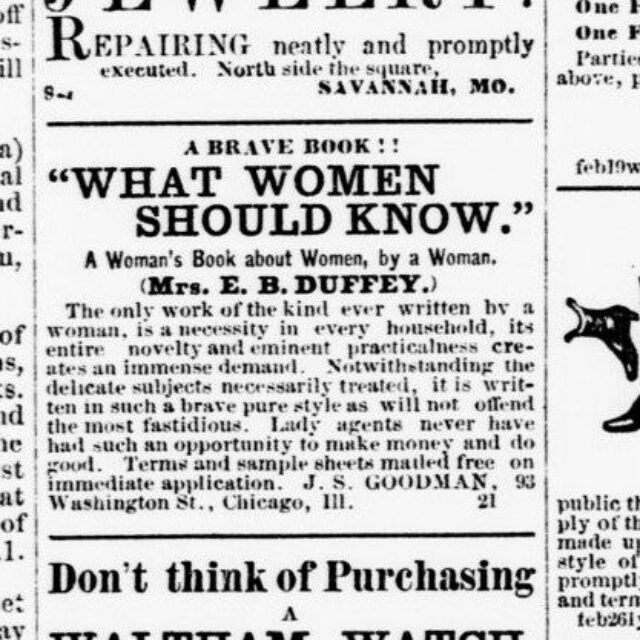

Second, many texts espouse professional knowledge of male physicians on information about health, reproduction, and medicine, making it a central feature on title pages. In a similar vein, texts aimed at women that were written by a woman were similarly promoted for containing “insider” knowledge and expertise on such topics. While it was not included in my initial corpus, I searched the Chronicling America database of newspapers for reference to a popular text by Eliza Bisbee Duffey: What women should know. A woman’s book about women (1873). Duffey wrote several pieces of advice literature for women including an etiquette book and response to Edward H. Clarke’s Sex in Education (1873). What women should know was advertised in periodicals across the country in the 1870s as the first prescriptive domestic and medical text for women written by a woman. Duffey’s work was published at the same time that the “Comstock Laws” were passed in the United States declaring contraceptives and obscene and explicit, making information about them liable to censorship and seizure by the United States Post Office and other federal bodies if circulated, advertised, or referenced in print material. As marriage manuals contain information about reproduction and family planning, it is an interesting genre in which one may observe effects of such censorship laws in the late nineteenth century. Or, as Stephanie Peebles Traver argues in (P)rescription Narratives: Feminist Medical Fiction and the Failure of American Censorship, the selective censorship of information for “rights-bearing citizens worthy of respect” exists along hegemonic divides of citizenship and personhood by race, class, and sexuality (17–18).

As Traver’s work notes, a key facet about marriage manuals is not just not just authorship, but audience: for whom are these marriage manuals created and what does this tell us about representative ideas of gender and sexuality in the nineteenth century? Who is left out of these texts and what is the significance of such absences? The initial corpus that I developed for this project is interesting, but–as I discovered with more research and time spent identifying other marriage manuals across archival repositories in New England and Pennsylvania–it is far from representative of this genre as a whole. The more research that I have done on this topic has made me aware of the importance of setting key parameters for date of publication, manual contents, and audience. These factors were not well known to me when I first began this project and, as a result, this corpus contains texts I now would not define as marriage manuals, like Havelock Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Indeed, this corpus represents a first iteration of my corpus based on my initial understanding of marriage manuals that as I develop further parameters for this collection, will include subdivision according to gender of author and audience, difference between popular medical and domestic manuals, and date of publication across the nineteenth century.

Word Embedding Models: Initial Observations + Questions

While many of the initial observations I had about marriage manuals were generated from curating a corpus and looking across OCR transcriptions for “noisy” data, I was interested in looking at these possible patterns at scale using word embedding models. My decision to use word embedding models as a specific form of computational text analysis–as opposed to topic mapping–is linked to my further interest in conceptual or semantic genealogies of gender, health, and disability. Genealogy is a form of critical inquiry that–building off Michael Foucault’s theorization–scholars use to tease apart the “messy conceptual complexity” of issues like in Peter Cryle and Elizabeth Stephens work on retracing normality from 1820-1950 in political, scientific, mathematical, and demographic studies (13) or Eunjun Kim’s careful genealogy of asexuality in psychiatric diagnoses from early sexology with descriptions like frigidity, sexual coldness, sexlessness, passionlessness (253). An important thread of scholarship in the history of sexuality and disability is the attention to the potential, limitations, and tension of studying historic materials and subjects using modern concepts and ideas like disability and gender. As language changes with time and usage, conceptual genealogies are a way to trace the semantic meaning of topics like those related to specific forms of identity and bodily configurations. While the word “asexual” was not used throughout the nineteenth century to describe a person who does not (or infrequently) experience sexual attraction, Kim’s work demonstrates that the concept of asexuality was prevalent in different texts, just using different words.

Word embedding models (WEM) is a form of computational text analysis using machine learning and natural language processing to map textual data onto mathematical models to predict and display semantic relationships between words in a corpus. WEMs are useful to understand words related to such concepts across a large corpus. To create a word embedding model for my corpus, I used the python tutorials developed by Avery Blankenship and the WWP team in Jupyter Notebooks for the Word Vector Toolkit. Designed as step-by-step tutorials, the WVT Jupyter Notebooks use the Gensim package in Python to clean a textual corpus and train a word embedding model. As someone who is still learning python and fairly new to the Gensim package, I used this opportunity to explore and test the effects of training models using different parameters. Based on my previous research using word embedding models in R on a corpus of LGBTQ+ finding aids, I mainly focused on testing the significance of changing the number of iterations in the training process. For the Gensim package, the variable is referred to as “epochs,” which corresponds to how many times over the text you want a model to be trained on. I tried three different settings: 5, 20, and 100. On a corpus that is under 3 million words like mine, changing this one variable does not hugely impact the time it takes to train a single model but it does have an effect on the results. For instance, here are the top ten words associated with the vector for marriage at different iterations in the training parameters.

V(marriage) at 5 iterations: womans (0.91), church (0.89), law (0.89), christian (0.89), religious (0.88), history (0.88), christianity (0.89), motherhood (0.87), basis (0.87), guide (0.86)

V(marriage) at 20 iterations: courtship (0.67), essentials (0.65), riage (0.65), consummation (0.63), mutual (0.62), matrimony (0.61), betrothals (0.61), law (0.60), puritan (0.60)

V(marriage) at 100 iterations: capture (0.69), barrenness (0.69), overgrowth (0.64), nonessentials (0.63), incompatibility (0.63), puritan (0.62), essentials (0.61), avowals (0.61), consanguinity (0.60)

Vectors for the query word “marriage” in word embedding models trained at different iteration values.

Each of these different vectors show different facets of semantic meaning for the word marriage, all trained on the same corpus but are the result of different training parameters for iterations. In this preliminary stage of my research, I am interested in using vector models to generate new questions and possibilities for further developing my corpus and research framework. Since gender is a particularly important question in my work, there are already interesting things to explore regarding different gendered roles in marriage that do not even start to touch on the relationship of gender and authority or gender and medical practice. In the examples from my WEM I use in this section, each query word represents one dimensions of the model that marks the relationship of one word with all the word in the corpus. This semantic relationship is modeled with vector math and the closeness is measured by a cosine value. The higher the value in brackets, the more closely associated with the query word it is in the WEM. If we look at the word vectors for the words wife and husband as the gendered roles in a marriage as defined and outlined in these marriage manuals, there are two very different forms of meaning that arise even at two different iterations of model parameters. While both wife and husband are categorized by relation to other familial roles, wife is more closely related to words about domesticity, like “house” but also “counsel” and “helpful.” On the other hand, husband is related to things outside the house, like “physician” and, in the model trained at 20 iterations, speaks of “submission” and “consultation” and “shalt.” As the majority of text in this corpus are written for women, the vector for husband denotes the relationship between wives and husbands where “submission” and “shalt” demonstrate patriarchal values of obedience and direction from men in domestic spheres. While word embedding models are non-deterministic in nature as it is simply a model of relationships related to proximity, training my models at different levels of iterations had an overall pattern: the higher the iteration, the more specific the word vectors, or at least, less general. I am interested to see if this trend holds up when increasing the size of the corpus and through retraining. While these are only preliminary examples of simple conceptual relationships that are not even related to medical practice or issues of health and sexuality, they demonstrate the interesting ways that word embedding models open up larger perspectives about concepts in a corpus in novel and exciting ways.

V(wife) at 5 iterations: husband (0.91), mother (0.89), father (0.89), house (0.89), friend (0.88), daughter (0.88), wifes (0.87), mistress (0.86), man (0.86), son (0.86)

V(wife) at 20 iterations: husband (0.73), widow (0.65), cleave (0.63), mistress (0.63), counsel (0.63), father (0.62), daughter (0.62), brother (0.61), helpful (0.61), sister (0.61)

V(husband) at 5 iterations: daughter (0.95), house (0.93), father (0.92), wifes (0.92), friend (0.92), mother (0.91), physician (0.92), mistress (0.91), wife (0.91), companion (0.91)

V(husband) at 20 iterations: wife (0.73), submission (0.65), consultation (0.65), wifes (0.63), casting (0.63), midwife (0.63), shalt (0.62), humor (0.62), devolves (0.62), poses (0.62)

Vectors for query words “wife” and “husband” in models trained at 5 and 20 iterations.

Conclusion: Next Steps + Future Research

As I continue to explore the applications of word embedding models in my dissertation research on marriage manuals and other forms of popular and domestic medical manuals in the nineteenth century, I am excited to develop a critical framework for the concepts I wish to trace related to authority, gender, audience, disability, and sexuality. Throughout the course of this project working with Professor Linker my understanding of the application of word embedding models to questions of materiality, classification, and genre has grown substantially. This project has allowed me to develop important frameworks that have informed my dissertation prospectus, acting as a sort of “test run” for the work that I am going to be doing on a much larger scale. I will be following many of the thematic questions that arose when I was working with the texts as material objects, only this time I am also working on looking at the relationship between modes of focus in digital scholarship: close and distant reading and how, when brought together with the interdisciplinary and overlapping information in marriage manuals, allow for critical research within the history of medicine and digital scholarship.

Sources Referenced

Brandt, Susan. Women Healers: Gender, Authority, and Medicine in Early Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023.

Cryle, Peter and Elizabeth Stephens. Normality: A Critical Genealogy. The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Fissell, Mary E. Vernacular Bodies : the Politics of Reproduction in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Johnson, Juniper. “Word Vectors for the Thoughtful Humanist Institute Data Preparation Guide and Checklist,” Women Writers Project, https://wwp.northeastern.edu/outreach/seminars/_current/handouts/word_vectors/data_checklist.html.

Kenlon, Tabitha. Conduct Books and the History of the Ideal Woman. Anthem Press, 2020.

Kim, Eunjung. “Asexualities and Disabilities in Constructing Sexual Normalcy.” Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, edited by Megan Milks and Karli June Cerankowski, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014, pp. 249-282.

Tavera, Stephanie Peebles. (P)rescription Narratives: Feminist Medical Fiction and the Failure of American Censorship. Edinburgh University Press, 2022.