Written by Claire Lavarreda

This NULab blog series, “Meet the Method,” serves to showcase some of the DITI’s publicly available learning resources. This installment focuses on Voyant Tools.

A staple of student life is the presence of exams. Regardless of the field, undergraduate and graduate students alike find themselves studying, reading, and writing throughout their chosen program, year after year. This past Spring 2024 was no exception for me, as I had to take qualifying exams as part of the World History track. A major component of this process was to read a large amount of books and summarize them over a year, resulting in a hefty file of notes by the end. Authors, book titles, summaries, citations, paraphrases, quotes—this document has it all, and remains a valuable resource that I plan to reference in the future.

Recently, I found myself scrolling through said document, searching for a citation that had escaped my brain. As I waded through the 185 pages, I began to wonder what my notes would “look” like. Did I repeat words and phrases over and over? Did I favor an author and reference them repeatedly? Were there filler words I relied on? Did I use new terms as time went on? Out of curiosity, I decided to explore the trends in my exam notes by visualizing them in Voyant Tools, a site used by the Digital Integration Teaching Initiative to teach students about computational text analysis.

Computational text analysis is a broad term for a variety of digital approaches and tools used to explore “the articulation of meaning (or meanings) embedded in written text.” (UC Berkley Social Science Matrix). Specifically, DITI resources on computational text analysis explain it as “reading” texts with computers: patterns, frequencies, networks, and connections all become visible through a variety of tools, such as Word Tree, Plot Mapper, MALLET, Google NGram, Lexos, and the aforementioned Voyant. Tools vary in complexity, and for my casual purposes, Voyant seemed to be well-suited for the task.

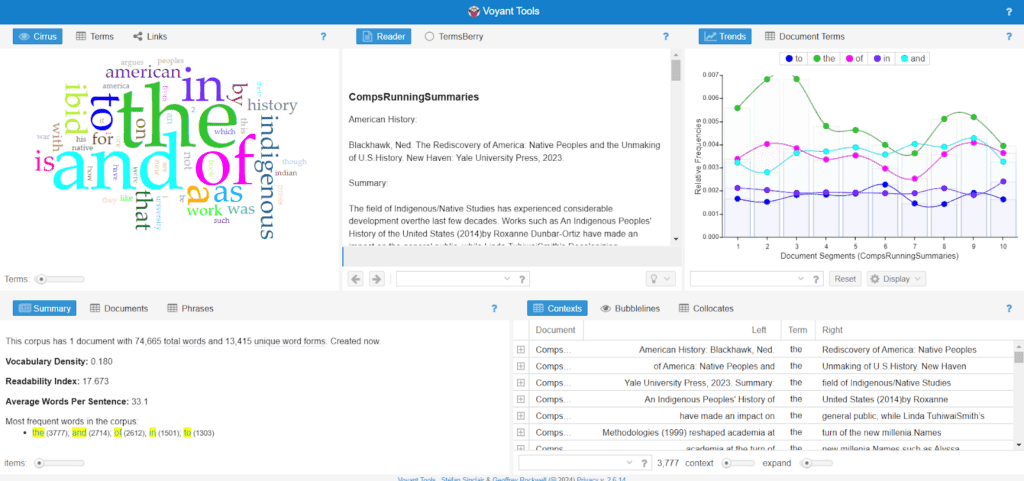

Following the slides and handouts available via the DITI Teaching Resources, I established my corpus (the exam notes) and the exploratory tool (Voyant). I then followed the steps as outlined in slides 21-27 to upload my corpus. Below is the initial result, which displays a word cloud in the top left, my corpus in the middle, word trends in the top right, a summary in the bottom left, and specific sentence contexts (showing the selected word with their surrounding words) in the bottom right.

Caption: A screenshot of the initial Voyant “dashboard” view. A small word cloud is visible in the top left, with terms like “the” and “and” dominating most of it.

The first result was dominated by terms like “the,” “and,” “to,” and “of,” which was not quite the visualization I was looking for, so I decided to remove filler words so I could see the actual concepts and terms I had been studying. This included words such as “like,” “a,” “and,” “if,” etc. In order to do this, I had to select the “define options” button in the top left word cloud box, and then select “stopwords” to add fillers to the “stoplist.”

Caption: A screenshot of Voyant’s stoplist editing window. Words like “a,” “and,” “if,” “in,” and “of” are visible.

Once that was done, my word cloud visualization totally changed, with the most frequently used terms now reflecting the topics I had studied for my exams. This included “indigenous,” “work,” “american,” “ibid,” and “history,” with smaller words like “books,” “spanish,” “borderlands,” “women,” and “colonial.”

Caption: A rainbow-colored word cloud with top words including “indigenous,” “history,” “work,” “american,” and “ibid.”

This was a simple, yet fascinating visualization for me, because it defied certain assumptions I had made about my own notes and learning. Though I knew my main fields, I did not realize how much emphasis I had placed on citation (noted in the large “ibid”) and sub-topics, such as “women,” “identity,” and “war.” This word cloud allowed me to view the connections between my topics more deeply, while also illuminating elements of my writing style, such as repeated use of “which” and “argues.”

Despite my personal love of word clouds, however, it should be noted that Voyant Tools has a variety of other visualizations, including graphs, bubbles, mandalas, collocations, and much more. Furthermore, multiple corpora can be uploaded to Voyant—for example, if I wanted to compare one set of notes to another, I could upload both documents. I decided to try another visualization, using Voyant’s topic modeling option. Topic modeling allows a viewer to get an idea of the text from a distance, displaying words that frequently show up together in the text. This allows a reader to identify themes in the corpus. To do this, I selected the panel tool button, scrolled to “topics,” and then adjusted the parameters to “run” 15 terms and generate 15 topics. The first ten results can be viewed below.

Caption: A screenshot of multi-colored topics, with terms like “indigenous,” “rediscovery,” and “native” occurring in the same section.

The topic modeling results displayed themes I expected, such as the co-occurence of terms like “american” and “american revolution,” as well as “indigenous” and “rediscovery.” Certain terms, however, I did not expect, such as “early,” “basin,” and “africa” occurring together, especially since I had not thought that Africa had played a large role in my study of the early Indigenous Americas. Upon revisiting some of the books on my reading list, however, it became clear that this was accurate—especially as it pertained to the historical trade of the greater Atlantic basin.

By using Voyant, I was able to visualize my learning in different and interesting ways. Computational text analysis in general encompasses a variety of tools and approaches, with several (such as Voyant, Lexos, Word Tree, and Word Counter) used by the DITI. Anyone interested in exploring their own notes, summaries, and essays should check out the tools and resources available via this linked handout!