COVID-19: A Catalyst for Sustainability

This course will incorporate lifecycle assessment of consumption to highlight the true cost of consumption. The discussion will address how individuals can promote long-term change to the benefit of our planet and people by simply allowing social and environmental justice values to guide their market behaviors. Topics will include the relationship between energy production and GDP, lifecycle assessment of consumption, and the relationship between sustainability and quality of life.

- Video: Introduction

Our present growth oriented economy fosters immediate gratification as a proxy for quality of life but does not account for the lifecycle impact of the production of an item. Instead, costs are externalized (e.g. environmental pollution, social exploitation), borne by vulnerable entities who implicitly subsidize the consumption of the end purchaser. From this perspective, market values indeed distort the true cost of consumption. Further, consumers unknowingly, as a result of their purchases, are then complicit in exacerbating social justice, environmental justice and economic equity issues, the three pillars of sustainability, in spite of their values to the contrary.

Since the start of 2020, COVID-19 has halted our wants. Social distancing and other safety protocols have significantly reduced consumption levels. For many, the forced simplicity of need-based consumption has provided an opportunity for observation and reflection and for some an opportunity for lasting value-aligned behavioral change. In the wider view, in this short period where human activity on a global level has dramatically slowed, communities have evidenced improvement in environmental quality. COVID-19 has facilitated:

- Recognition that much of our consumption is unneeded

- Realization that our actions are interconnected and we are interdependent

- Understanding that our most significant impacts are local

This course will incorporate lifecycle assessment of consumption to highlight the true cost of consumption. The discussion will address how individuals can promote long-term change to the benefit of our planet and people by simply allowing social and environmental justice values to guide their market behaviors. Topics will include the relationship between energy production and GDP, lifecycle assessment of consumption, and the relationship between sustainability and quality of life.

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Explain the relationship between social norms and economic outcomes and from this appreciate the role of stakeholder engagement in promoting pro-environmental policy.

- Understand the embeddedness of economic growth, GDP, in decision-making.

- Assess the life cycle impact of consumption.

- Perform a cost-benefit assessment.

- Recognize the significance of marketed demand and planned obsolescence in defining economic growth.

Our focus in this module is to think beyond the economic framework that we observe and view the system as a social construction that is institutionalized and operationalized in our culture. For instance, are we naturally competitive or cooperative? Evidence reveals that we are most happy in cooperative systems. Though competition exists it is the intent of competition that matters. Our natural inclination is not to do harm. However, we can be socialized into competition and if we give aggression legitimacy we can promote value in the attribute. Since aggression will, by definition dominate passivity, social norms can dictate how and if aggression is a desirable attribute.

How we view non-human life dictates whether we view our co-existence as stewardship or dominance and from this the affect on how we measure and view our economic system follows.

Consumption and economic growth

Cultural orientation toward consumption implicitly surfaces the perception of the human relationship with the environment as either one of symbiosis or dominion. In the case of the former, arguably stewardship would prevail. In the context of perceived dominion, the economic system would likely fail to assess intrinsic value of resources, as resource value would be dictated based on the value of the natural resource to the human system. Further and significant, the inclusion of time effects as they relate to the preservation and or regeneration of resources would determine if one period’s stewardship or dominion impacted future access, availability, and viability of a resource.

Our present global society builds on an institutionalized western perspective of the environment as a resource for human use; this in turn is implicit to global economic systems and their focus on GDP. GDP is embedded within the prevailing neoclassical discussion of the production possibilities frontier (PPF) and similarly, our policy interest in ensuring that we seek to maximize production subject to resource constraints at any given point in time. In the case of production this conforms to policy, monetary and fiscal, that seeks to maintain or establish the economy at its peak in business cycle terms, which is equitable to the attainment of potential GDP.

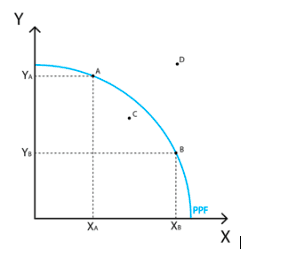

The underlying and guiding assumption of production and consumption decisions is premised on neoclassical consumer theory, which defines individuals in an economy as having insatiable desires to consume. This assumption is reflected in the production possibilities frontier (PPF) where efficiency is defined as any production combination found on the PPF line (Figure 1). On this line, the economy is maximizing production relative to resource constraints. Combinations of output along this can only be attained by allocating the resources in a way that maximizes production relative to inputs (e.g. land, labor and capital). To the extent that the allocation of resources at a given point in time considers intergenerational equity and threshold extraction rates consistent with the prevention of resource depletion, and enables repopulation for renewable resources, the trade-off decisions may or may not be consistent with sustainable resource utilization.

Further, to the extent that a society is taught or maintains the social norm of stewardship and thus satiation of needs relative to that of wants, the efficient allocation of resources may not embody the maximum production. Instead an economy may not fully use observable resources given consideration of their availability from a long-term perspective.

Figure 1: Production Possibility Frontier

MCluney (2008) suggests that reduction in consumption is needed by developed countries to reduce the environmental burden and social justice implications of the present trajectory of consumption within those countries. He notes that there is a moral dilemma at present, given that developed countries have been able to grow and develop high standards of living by environmental exploitation but are now seeking to eliminate the same channels that enabled their development within the developing world. Addressing population pressures and finite growth prospects, he concludes with questions that surface the significant role of consumption: “Will the industrial world be willing to alter its own system to benefit the starving billions elsewhere? How much should the industrialized countries be willing to sacrifice for the sake of the underdeveloped world? Is it moral to conclude that we should not make such sacrifices, or is the very question born of a fallacious understanding of what it takes to live well (McCluney, 2008)?”

Consumption and sustainable growth

In most western developed countries, consumption is a significant driver of GDP growth. To the extent that GDP is the standard metric of economic progress and economic progress is a focus due to the perception that progress equates with a higher standard of living, consumption has also become a targeted metric. From this perspective, nearly everything in an economy can be related to consumption, from maintaining full employment, to maintaining stable inflation and low interest rates, to the built-in obsolescence of the goods we purchase. Even the assumptions embedded in economics incorporate consumption: consumers are assumed to have insatiable wants.

Marketing and advertising have played a strong role in fostering consumption by creating marketed demand, which essentially is demand that arises as a result of marketing and advertising. However, the responsibility of consumption has not been fostered, developed, or perhaps even understood by consumers.

Consumers have become increasingly distanced from the production process of the goods they are consuming, and as a result, they are not cognizant about the impact that their consumption demand has on the degradation, exploitation, and depletion of planetary resources. Instead, what consumers are aware of is price. Fundamentally, consumers have focused on market price and have delegated the inclusion of value parameters, including environmental and social costs, to producers, but producers are incentivized to minimize cost and maximize return. Externalizing costs are beneficial to producer profit maximization. As a result, unfortunately, there is a failure in the incentive matching between consumers and producers. In most cases, due to the externalizing of costs and externalities, market prices do not reflect the true cost of a good. Individuals can purchase more resources because not all costs are captured in their production; in essence, reliance on market prices can enable unsustainable consumption (Venkatesan, 2017).

From this perspective, consumption plays a significant role in the sustainability of the planet. Responsible consumption is requisite, and this can be promoted through education and the coalescing of the consumer base, where the common ground can be founded both on the self-interest assumed in economics and the trending cultural value of holistic assessment.

Consumption choices are based on demand and supply of a good and are identified with satisfying a need or a want. The impact of consumption decisions can be significant when there is asymmetry of information; fundamentally, there is a relationship between economic and environmental outcomes and consumption choices. Purchases affect labor and environmental resource use. However, most purchase decisions are made through a market mechanism, where the consumer is not explicitly made aware of the entire production process, prices are inclusive of only market costs of production, exclusive of the impact of externalities, and waste is not a factor in the consumption decision. This limitation in information transparency often creates a disconnect between the social and environmental justice sensitivities of a consumer and the realities of their consumption choice in enabling and maintaining the values that they espouse.

Consumption decisions can have a significant ripple effect throughout a single economy as well as the finite global resource base. Consider for example the life cycle of milk cartons. Polyethylene lined, printed paper milk cartons have been created for the transport and preservation of milk from the production to the consumption stage. However, the components of the carton were not developed with waste disposal in mind; rather, increasing distribution and sales were the rationale for the carton. As a result, largely related to the focused basis of its creation, the milk carton serves a consumption purpose without consideration of the impact to the environment and potential future human and animal health due to its non-biodegradable or re-usable composition. This illustration on a broader consumption scale provides a simplified perspective to evaluate the underlying values captured in consumption decisions. From this perspective, production for consumption may be expressed as a myopic activity, focused on near- term satiation of a need or want to the exclusion of the evaluation of the impact or ripple effect of the satiation.

References

McCluney, R. (2008). Population, Energy, and Economic Growth: The Moral Dilemma. In Newman S. (Ed.), The Final Energy Crisis (pp. 151-161). Ann Arbor, Michigan: Pluto Press.

Venkatesan, M. (2017). Economic Principles: A Primer, A Framework for Sustainable Practices. Charlotte, SC: Kona Media & Publishing.

- Reading: Kern Alexander, “The Purpose of Education: Peace, Capitalism and Nationalism,” Journal of Education Finance

- Reading: Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza and Luigi Zingales, “Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes?,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives (pages 23-48)

- Reading: Manoucher Parvin, “Is Teaching Neoclassical Economics as the Science of Economics Moral?,” The Journal of Economic Education

- Reading: Charles K. Wilber, “Teaching Economics as if Ethics Mattered,” London: Anthem Press

- Reading: Robert H. Nelson, “Sustainability, Efficiency, and God: Economic Values and the Sustainability Debate,” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics

- Reading: Sharon Beder, “Valuing the Environment,” Engineering World

- Lecture: Values, Behaviors, and Economic Outcomes

Topic 1 Assignment 1

This assignment is focused on the readings provided. Please address each question as a short essay and cite/reference the readings using APA style.

How did you view the role of education in society prior to reading Alexander (1994)? Did you assess why education had value in a society or default to it being a necessary aspect of life without explanation? Is education fundamentally focused on occupation and financial well-being specific to accumulation? How does this relate to the perspective of culture noted in Guiso et al (2006)?

Parvin (1992) and Wilber (2004) address the limitations of neoclassical economics, the framework that is the basis of present instruction in Principles courses, where individual action is assumed to be rational and focused on benefit maximization. These authors offer similar perspectives. How does the teaching of neoclassical economics foster a singular focus in the economy and relate to the defining of human behavior?

In adding the perspective of Nelson (1995) and Beder (1996), how can we modify our present system to account for human dependency on the environment? Is sustainability consistent with the present definition of economic progress (GDP focused, resource/technology dependent growth)?

Readings referenced are in Module 1: Readings. (Read in order provided)

Alexander, K (1994). The Purpose of Education: Peace, Capitalism and Nationalism. Journal of Education Finance, 19(4), 17-28.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23-48.

Parvin, M. (1992). Is Teaching Neoclassical Economics as the Science of Economics Moral? The Journal of Economic Education, 23(1), 65-78.

Wilber, C. (2004). Teaching Economics as if Ethics Mattered. In Fullbrook E. (Ed.), A Guide to What’s Wrong with Economics (pp. 147-157). London: Anthem Press.

Nelson, R. (1995). Sustainability, Efficiency, and God: Economic Values and the Sustainability Debate. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 26, 135-154.

Beder, S. (1996).Valuing the Environment. Engineering World, December, 12-14.

Topic 1 Assignment 2

These three assignments provide an opportunity to make the readings for this week tangible. The first two focus on resource scarcity and abundance, while the last provides an entry point into Ecological Economics. Ecological Economics views the human system as subset of the environmental system, whereas, standard neoclassical economics positions the environment as a resource for use within the human system. It is important to note that Ecological Economics is an alternate way of framing economic systems.

Please write your answers to each of the three questions sections as essays not question by question responses. Use appropriate citations and include full references. The writing stye for this class is APA.

1. Read the original article on the Tragedy of the Commons” by Garrett Hardin , published in 1968 consider how well its arguments apply to global environmental problems today. Consider the implications of Hardin’s argument for theories of property rights and the appropriate role for governments or international agencies in protecting the global commons. What are the implications of the “tragedy of the commons” for approaching difficult current problems like global climate change?

2. The U.S. Geological Survey has published a report on the historical prices of many metals in the United States over a 40-year period, Metal Prices in the United States through 2010

Summarize the historical price trends (in constant dollars) for aluminum, copper, iron ore, mercury, and silicon. Would you conclude that the price of these non-renewable resources has increased or decreased over time? Are the prices reflective of the scarcity/abundance of metal (you may need to access outside resources; please source and cite your references)?

3. Read the paper Three General Policies to Achieve Sustainability” by Robert Costanza.

What are the three environmental policies advocated by Costanza? Summarize how a natural capital depletion (NCD) tax would work. Why does Costanza suggest that a NCD tax should be welcomed by both technological optimists and skeptics? What are environmental assurance bonds? How could environmental assurance bonds help to deal with the uncertainties of estimating environmental externalities?

In this course we will be addressing the role of consumption on the environment. To facilitate the tangibility of the impact of consumption choices on sustainability, I would like you to pick a beverage that you like to consume and that there is sufficient information on with respect to contents, container and producer that you can evaluate a product lifecycle of the container and the beverage from raw material to waste. Your selection can include any product but water in single-use plastic bottles.

The best products to pick given the time constraints on our course are manufactured by public companies (listed on the stock exchange) because they will have accessible financials and details with respect to risk and growth strategy. Additionally, accessible ingredient labels will also be useful.

I would like you to share the product you have chosen, why you like to consume it, how much you consume of it and how you typically dispose of the container in your post for Life Cycle Assessment Phase One Discussion. Please ensure you provide a description that explains your product in a minimum of 200 words and a maximum of 350. In addition, please write your perception of the sustainability of the beverage you have chosen without using any outside resources. Follow the outline below and limit your discussion in this assignment to 1,200 words. Please write your essay as an essay not a listing of answers to the questions. This writing assignment requires no outside resources, so no citations/references are required. However, when references are used going forward, please use APA style. Your essay should be posted to Life Cycle Assessment Phase One Assignment.

Life Cycle Assessment Phase One Discussion

Please share the product you have chosen for your life cycle assessment, why you like to consume it, how much you consume of it and how you typically dispose of the container in your post for Life Cycle Assessment Phase One Discussion. Please ensure you provide a description that explains your product in a minimum of 200 words and a maximum of 350.

-Name and describe the beverage.

-Who is the manufacturer?

-Why do you like to consume it?

-How much of the beverage do you consumer weekly?

-What is the nutritional value of the beverage?

-How sustainable is the company and beverage? Explain your answer.

-What do you do with the container after you consume the beverage

-What happens to the container?

Globally, economies are measured in relative terms with respect to a single economic indicator, the gross domestic product (GDP). This indicator, which was created to measure output, has become a synonym for standard of living, in direct opposition to the caution related to the same put forward by its creator, Simon Kuznets (1934). Further, quantification of economics in the decades that followed its deployment has successfully facilitated the perception of economics as a science and distanced the discipline from its moral philosophical roots. Instead of the behavioral discipline of economics providing evaluation and policy based on an explicit normative framework of seeking to attain societally optimal outcomes related to ecosystem symbiosis and quality of life attainment, inclusive of resource conservation and mental and physical optimality, economics has been molded by mathematics to project an objective observational stance. The latter however is an implicit normative judgement that has promoted business as usual without conscience-based responsibility. Failures in the market are labeled as “externalities” and the teaching of economics has endogenized marketing and profit-making by legitimizing that individuals are insatiable and driven by greed. That these assumptions, which are referenced as theory, are social norms borne into existence through social construction are not addressed.

With 70 years of this standardized teaching, the economy has been molded by theory and its behavior is consistent with insatiability, with high resource use, excess production and consumption, as well as, a lack of acknowledgement for non-market costs, such as the responsibility for waste. Arguably, this reality provides an opportunity for the discipline to acknowledge its relevance with respect to issues affecting global environmental health, as indeed, it is the production driven model along with an exclusion of moral responsibility that has created the social and environmental justice issues of the present and has been a direct contributor to Climate Change.

Even though a behavioral science, economics has been taught as though it is an optimization discipline, and that incentives like utility and profit maximization are immutable drivers of human behavior. Students are typically presented with a single perspective that reinforces the economic framework in operation. However, the teaching also bounds the rationality of the student to the extent that there is no critical assessment of the prevailing economic system, no discussion of moral responsibility of fundamental purpose other than accumulation. As early as 1938 Beach stated,

It has been the policy of many teachers of economics that beginners in economic theory should be taught only one theoretical explanation of each phenomenon These teachers feel that the acquaintance of the student with other explanations can be postponed until the student has become more familiar with economics in general and therefore has a better sense of judgment. The existence of other theoretical explanations can be mentioned, and this, it is thought, should be sufficient to keep the student aware of the fact that there are other sides to the story.

The effectiveness of this policy might be questioned. Even if the existence of other theories is mentioned, the significance of this existence is very seldom appreciated. Elementary students look for definite answers to their problems, and, lacking the power of discernment, will accept the one theoretical explanation as sufficient. If the students do not continue in this subject, this one explanation will always be the explanation. If the students continue, they will tend to have a bias in respect to this one explanation.

Therefore, for those phenomena for which no one theoretical explanation is entirely satisfactory, instead of offering one theory, which may indeed be the best, would it not be better to develop the power of discernment of the student by suggesting more than one theory? Two explanations should be enough, and if they could be introduced by emphasizing certain contrasting features, the additional time need not be great, and the original explanation may be made clearer. Perhaps the most important job of the teacher in social sciences is to develop the students’ power of discernment. The students must learn that one idea does not contain the whole truth; and when this is learned, the students’ progress will be more rapid (515).

In the present period, researchers have noted that the teaching of economics has not deviated much over the past 50 years highlighting that the profession of the teaching of economics has lagged with respect to alignment of content with contemporary issues ( Bowles and Carlin, 2020). This is a lost opportunity and a problem. The exclusion of application and limited tangibility in the classroom teaching of economics has limited recognition of the significance of economic literacy. Given that introductory economics is typically a requirement at most institutions, non-tangible and commoditized teaching does not allow the profession the opportunity to be relevant.

More broadly, a few courses in undergraduate economics, and perhaps only an introductory course, are often the only interaction that the college graduates of tomorrow will have with the economics profession. Because they are the only opportunities that academic economists will have to educate the citizens and voters of tomorrow, they deserve our best efforts (Becker, 2000, 117).

GDP

By definition, GDP measures the market value of all (gross) final goods and services (product) produced within a country (domestic) at a specific point in time. From this perspective, GDP provides an aggregate value but no detail with respect to the distribution of goods and services, quality or standard of living of a country’s inhabitants. However, given the relationship between employment, disposable income and consumption, there is an implied connection between employment growth and GDP. As a result, employment is a significant predictor for GDP growth and to the extent that increased GDP growth is a target metric for countries relative to their measurement of progress, employment growth and quality are also routinely evaluated. GDP can be calculated by assessing total income generated in an economy or total expenditures made within an economy at a specific point in time. The components of the expenditure calculation of GDP include consumption (C), investment (I), government (G) and net exports (X – M), the formula for which is exports minus imports.

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

C: Consumption spending, C, is spending by households on goods and services, with the exception of new housing. Included in household expenditures are durable and non-durable goods as well as medical care and education.

I: Investment spending consists of the purchase of goods and services that will be used in the production of future goods and services. The expenditures include production facilities, inventory and new housing.

G: Government spending includes spending on goods and services by local and state and the national government, but it does not include transfer payments. Transfer payments do not reflect a direct purchase of a good or service; rather they reflect a reallocation of tax dollars. The expenditures of transfer recipients are already included in consumption spending, justifying their omission from Gin the calculation of GDP.

(X – M): Net exports reflect the net amount of purchases by foreigners of domestically produced goods (X) relative to the amount of foreign goods purchased in the domestic market (M). Net exports provide the status of the balance of trade between countries and are influenced by and also as a result of relative demand between trading parties, influence foreign exchange rates. Foreign exchange rates reflect the demand of one currency relative to another.

GDP is a measure of production capacity within a nation’s domestic borders and what it essentially captures is the total value of goods and services sold at a specific point in time. In the United States, consumption expenditures account for more than 65% of GDP. Because prices change routinely, the value of GDP is found in its growth rate period to period and in comparison, at a point in time to another country’s GDP values. This comparative evaluation has become a proxy for the economic strength of a country. As an aggregate measure, it does not capture the changes in quality of life or standard of living or even income distribution, these are significant limitations that were noted by developers of the indicator. However, since the 1940s has in spite of its known limitations, GDP has been the international metric for economic progress. Given the significance of consumption in the calculation of GDP as well as the focus on GDP as an indication of economic strength, consumption is a significant driver of economic growth and as a result a focal point of monetary and fiscal policy.

References

Beach, E. (1938). Teaching Economics. The American Economic Review, 28(3), 515-515.

Becker, W. E. (2000). Teaching Economics in the 21st Century. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(1), 109-119

Bowles, S. and Carlin, W. (2020).What Students Learn in Economics 101: Time for a Change. Journal of Economic Literature, 58(1), 176-214.

Kuznets, S. (1934). National income, 1929–1932. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

- Reading: Diane Coyle, “The Future: Twenty-first-Century GDP,” Princeton University Press. (pp. 123-146)

- Reading: Éloi Laurent, “Good and Bad Indicators: The Case of GDP,” Princeton University Press

- Reading: Madhavi Venkatesan and Giuliano Luongo, “SDG 8: Sustainable Economic Growth and Decent Work for All, Ch.2” Emerald Publishing

- Reading: Madhavi Venkatesan and Giuliano Luongo, “SDG8: Sustainable Economic Growth and Decent Work for All, Ch.3″ Emerald Publishing

- Reading: Joe Earle, Cahal Moran and Zach Ward-Perkins, “Econocracy: The perils of leaving economics to the experts,” Manchester University Press

- Reading: Erald Kolasi, “Energy, Economic Growth, and Ecological Crisis,” Monthly Review

- Lecture: EconEd 2019

Assignment 3

Read Chapter 1 of the report dealing with “Drivers” of environmental trends. This gives an overview of trends in population growth, economic development, energy use, and resource demands. What do you think are the most important environmental threats facing humanity? Does the report offer a basis for hope that these threats can be successfully controlled or reversed? What kinds of policies are most relevant in responding to environmental challenges?

Please provide a short essay of 450 to 500 words. You may use outside resources to strengthen your position and perspective. For all in-paper citations and references, please use APA style.

Discussion Collapse or Sustainable?

In 2002 the authors of the original Limits to Growth model published Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update.

Browse through he synopsis including the last sections on “Transitions to a Sustainable World” and “The Sustainable Society”. Briefly discuss the view of sustainability. Do you believe that the world is headed towards a “collapse” or “sustainable world” scenario? What kinds of policies might make the difference?

Behavior, supply and demand and elasticity

Equilibrium defines the market price and is depicted as the point where supply and demand intersect. However, the price that is found at this price may be merely a reflection of asymmetry of information, who has the greater market power (suppliers of consumers) and elasticity.

Elasticity is a measure of the sensitivity of quantity to a change in price or income. It is embedded in the shape of the supply and demand curve and, as a result, is a significant influence on market equilibrium. Absolute elasticity can determine the impact of a consumer tax on purchasing behavior, while relative elasticity between supply and demand can determine which party will bear the larger share of an imposed tax.

Mathematically,price elasticity is the ratio of the percent change in quantity divided by the percent change in price. Because both the numerator and denominator are stated in percentage terms, elasticity is stated numerically relative to the value of 1. If the percentage change in the quantity is equal to the percentage change in price, elasticity will be equal to 1, which is referred to as unitary elastic. If the percentage change in quantity is greater than the percentage change in price, the absolute value of elasticity is greater than 1 and price elasticity is referred to as elastic. The percentage change in quantity as a result of the percentage change in price exceeds the percentage change in price, reflecting that consumers are opting out of the consumption of the item. If the percent change in quantity is less than the percent change in price, elasticity is less than 1, and supply or demand is referred to as inelastic. The quantity response is relatively insensitive to changes in the price.

Elasticity can also be perfectly elastic or perfectly inelastic. Perfect elasticity refers to those instances when the quantity response is infinitely large for a small change in price. Perfect inelasticity refers to those instances where there is no quantity response to price changes.

Elasticity affects the degree of behavior change (to promote pro-environmental behavior) related to policy. For example, if a carbon tax is instituted but tax was relatively low, it might impact only the most price sensitive people, those with the least income but have no impact on the behavior of the majority. For the tax to have an impact it would have to eliminate all elastic consumption (non essential items) leaving only essential consumption. This would make the prices of essential goods high and reduce overall consumption but it would impact people differently. The tax would be regressive, people on the lower income spectrum would be the most adversely impacted. This is why the Economists Statement on Carbon Dividends notes that there should be a subsidy for lower income families. If you read the statement, it also requests that taxes be imposed and increased routinely. Why? Because prices can be normalized quickly, so that behavior change may not take affect in the manner desired unless, prices continue to impose limits on consumption.

Elasticities tend to increase over time (become more elastic), as firms and customers have more time to respond to changes in prices. Although a company may face an inelastic demand curve in the short run, it could experience greater losses in sales from a price increase in the long run. Over time customers begin to find substitutes or new substitutes are developed. However, temporary price changes may affect consumers’ decisions differently than permanent ones. The response of quantity demanded during a one-day sale, for example, will be much greater than the response of quantity demanded when prices are expected to decrease permanently. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that elasticities differ at the firm versus the industry level. It is not appropriate to use an industry-level elasticity to estimate the ability of only one firm to pass on compliance costs when its competitors are not subject to the same cost.

Trade-offs, Opportunity cost and Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

If a carbon tax is imposed, it is essentially creating a trade-off between goods. Goods that are taxed may be substituted with goods that are not based on elasticity of consumption. When a trade-off is made, an individual is incurring an opportunity cost, which is essentially the value that they would have received for the choice that they did not make. Given the assumption of rational behavior, this implicitly means that the choice made by a consumer provides them with greater benefit than the choice that they did not make. How we actually assess the costs and benefits of the choice made relative to the choice forgone is Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA).

CBA is an art not necessarily a science; however, it has been developed in the environmental assessment arena to follow a formulaic process that is dependent on market values. This is likely the single most significant limitation of CBA analysis. If the market supply and demand curves reflect society’s true social cost, then a laissez-faire market (i.e., one governed by individual decisions and not government authority) will produce a socially efficient result. However, when markets do not fully represent social values, the private market will not achieve the efficient outcome; this is known as a market failure. Market failure is primarily the result of externalities, market power, and inadequate or asymmetric information. Externalities are the most likely cause of the failure of private and public sector institutions to account for environmental damages.

Externalities

Externalities occur when markets do not account for the effect of one individual’s decisions on another individual’s well-being. In a free market producers make their decisions about what and how much to produce, taking into account the cost of the required inputs — labor, raw materials, machinery, energy. Consumers purchase goods and services taking into account their income and their own tastes and preferences. This means that decisions are based on the private costs and private benefits to market participants. If the consumption or production of these goods and services poses an external cost or benefit on those not participating in the market, however, then the market demand and supply curves no longer reflect the true marginal social benefit and marginal social cost. Hence, the market equilibrium will no longer be the socially efficient outcome.

Externalities can arise for many reasons. Transactions costs or poorly defined property rights can make it difficult for injured parties to bargain or use legal means to ensure that the costs of the damages caused by polluters are internalized into their decision making. Activities that pose environmental risks may also be difficult to link to the resulting damages and often occur over long periods of time. Externalities involve goods that people care about but are not sold in markets. Air pollution causes ill health, ecological damage, and visibility impacts over a long time period, and the damage is often far from the source(s) of the pollution. The additional social costs of air pollution are not included in firms’ profit maximization decisions and so are not considered when firms decide how much pollution to emit. The lack of a market for clean air causes problems and provides the impetus for government intervention in markets involving polluting industries. Hence carbon taxing and cap and trade programs.

So, we have come full circle. Prices determine how much we consume but they may not (often are not) reflective of the true cost. Regulation in the form of taxes or constraints (cap and trade) seek to limit the amount purchased but if they are not aggressive enough or not consistent in execution, behavior may adjust temporarily but not change permanently due to elasticity, allowing the very same externalities that conditioned regulation to be maintained.

- Reading: Jack Reardon, Maria Alejandra Caporale Madi and Molly Scott Cato, “Economic Value: Pluralist, Sustainable and Progressive,” Pluto Press

- Reading: Jack Reardon, Maria Alejandra Caporale Madi and Molly Scott Cato, “Sustainability, Resources and the Environment,” Pluto Press

- Video: Wasted: The Story of Food Waste

Please watch Wasted: The Story of Food Waste

“Some of it is, ‘I don’t want that, do I really want leftovers from last night? Nothing wrong with the food, it’s probably going to taste okay, but I had it last night and so I have to have it again tonight? We’ve got enough money to buy a whole brand new meal,’ so that’s part of it, a wealthy society.“

“To me, it’s sort of funny that wasting food is not taboo.”

“At the moment, we are trashing our land to grow food that no one eats.”

“A large part of dumping is simple economics. It’s cheaper to throw it away than to do something more constructive.”

“What we need is to believe that wasting food is not acceptable. It comes down to citizen morals. It comes down to cultural attitudes, essentially.”

Following your viewing of the film and reflecting on the above quotes, address the following:

How does price affect food waste? Is food priced appropriately? Reflect on the resources to produce relative to its consumption value and waste.

How does the perception of food as inanimate impact the perception of waste? If people were made aware of the life that was taken in the creation of food, would that establish a moral framework for responsible food production and consumption? Why, or why not? Explain.

Please limit your response addressing the questions provided to 450 to 650 words.

Typically, externalities are characterized as negative, signifying that the externality yields an adverse outcome. These externalities are referenced as being negative externalities. However, there is a potential that a positive outcome could be generated leading to a positive externality. In the discussion of externalities, it is often assumed that market participants perceive the externalities generated by their actions as acceptable due to their focus on the immediate gratification of their needs. For the producer, this equates to externalizing the cost of the disposal of waste products into waterways and the air where no cost is directly borne to adversely impact profits, but arguably intertemporal costs can be assessed that may impact the enjoyment and longevity of multiple life forms and generations of human life. For the consumer, the externality can be evaluated in the indifference to waste creation at the point of the consumption decision or even the externalities associated with the production of the good or service being purchased. In the case of the former, the cost of the disposal of packaging material is typically marginal to zero, relatively negligible, but disposal creates a negative externality in the landfill, incinerator, or recycling plant that could have been avoided with a thoughtful exercise of demand.

At present, the type of internalizing of externalities that has occurred has been limited to quantifying the externality to an overt cost. However, to the extent that the costs may remain understated and the market mechanism is not cognizant and focused on the elimination of the externality-based cost but rather the minimization of overall costs, this process has yielded suboptimal outcomes. For example, assume that a firm produces ambient pollution as a result of the incineration of waste. If a governmental regulatory body institutes a fee or cost for pollution, effectively charging the firm for the ability to pollute the air, the producer is able to delegate responsibility for environmental stewardship to the price of pollution. Additionally, depending on the demand for the service offered, the producer may be able to not only transfer the costs now associated with polluting activity to the consumer, but may also be able to maintain the pollution level. Assuming that the good is a necessity, the consumer is inelastic to the change in price and maintains the needs quantity of the good. In this example, the negative externality related to internalizing the cost has not changed. Instead, only the responsibility of pollution has been transferred to a cost, revenue to the regulating body has been generated, and the consumer has suffered erosion in his overall disposable income and purchasing power. The impact of the latter outcome may be an unexpected contractionary phenomenon to GDP. Fundamentally, the consumer has continued to maintain demand arguably because the complete impact of the externality being created by their consumption is not understood.

Externalities are defined as a type of market failure based on the premise that optimal social outcomes result from individual economic agents acting in self-interest. However, if instead of being a market failure, externalities could be evaluated to assess and develop an optimizing strategy between individual interests and enhanced social outcomes, externalities could be internalized within the market model as a preference. Perhaps externalities only indicate a lack of holistic awareness on the part of the consumer and producer or a cultural bias toward immediate gratification. These characteristics can be potentially modified through education. Optimal and universally acceptable strategies could then be adopted to promote sustainability.

The success of this internalization strategy relies on the development of the educated rational economic agent as a consumer. If consumers are aware of the responsibility inherent in their consumption and are aware of the environmental and social impact of production processes, consumer demand can create the coalescing framework to augment preference to exhibit demand for sustainably produced products. The augmentation in demand does not allow for the opportunity of delegation of responsibility of pollution capacity to a cost or alternatively, the incorporation within a cost minimization framework. As a result, the change in preference and subsequent modification in demand promotes the development of market outcomes that are environmentally and socially optimal from the position of what is supplied.

The lack of inclusion of externalities in the cost assessment or consumption expense of a particular good, leads to the undervaluing of that good and potential for both over consumption and heightened waste. As depicted in Figure 1, along a product lifecycle, each step of the lifecycle may have costs that are not captured in price because firms have no incentive to include costs that they do not need to address, their focus is profit maximization (investor returns) and individuals presently are assumed to be incentivized to maximize consumption subject to an income constraint—the lower the prices the more of their insatiable desire to consume can be fulfilled. Lifecycle assessment enables evaluation of a process from the stance of an impartial bystander and given the preexisting moral responsibility of the observer, offers the opportunity to internalize externalities in production and consumption that are contributors to environmental and social justice, attributes of sustainability.

In this second stage of you lifecycle project, determine the primary inputs into production, the value of consumption, and the impact of waste. Along this evaluation process, address the time of each stage. Is consumption relatively short compared to production of resource inputs and waste? This short film may assist you as well, The Story of Bottled Water. Write an overview of the stages of production, consumption and waste related to your beverage and its container. With respect to the beverage evaluate the major inputs and nutritional value of the product. Your overview should be between 1,000 to 1,250 words; please cite and reference materials you use.

Evaluating Lifecycle Impacts through an assessment of plastic

Environmental Impact Assessment – LCA (Life Cycle Assessment): What is it?

Environmental assessment is a procedure that ensures that the environmental implications of decisions are taken into account before the decisions are made. Environmental assessment can be undertaken for individual projects, such as a dam, motorway, airport or factory, or for public plans or programs. The common principle is to ensure that plans, programs and projects likely to have significant effects on the environment are made subject to an environmental assessment, prior to their approval or authorization. Consultation with the public is a key feature of environmental assessment procedures.

Significance of a Life Cycle perspective

Today, the impact of products and services on the environment has become a key element of decision-making processes. Instead of considering only fragments of environmental impacts such as those resulting from production, use or disposal, societies of the future will have to consider a product’s life cycle as a whole. Against this background, ‘Life Cycle Thinking’ has become a central pillar in environmental policies and sustainable business decision-making. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a tool to review the environmental impact of products throughout their entire life cycle – (from cradle to grave) – from raw material extraction through transport, manufacturing and use all the way to their end of life. In order for the analysis to be meaningful, it is essential to use consistent and reliable data. Therefore, a crucial first step in the LCA process is the production of a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI). The LCI is an extensive set of data on the relevant energy and material inputs and environmental outputs.

E-LCA is a time tested assessment technique that evaluates environmental performance throughout the life cycle of a product or from performing a service. The extraction and consumption of resources (including energy), as well as releases to air, water, and soil, are quantified throughout all stages. Their potential contribution to environmental impact categories is then assessed. These categories include climate change, human and eco-toxicity, ionizing radiation, and resource base deterioration (e.g. water, non-renewable primary energy resources, land, etc.). The Life Cycle Initiative played a key role in the development of the life cycle assessment midpoint-damage framework, which conceptualizes the linkages between a product’s environmental interventions and their ultimate damage caused to human health, resource depletion and ecosystem quality – information which is of critical importance to decision makers.

- Reading: Zoe Carpenter, “The Toxic Consequences of America’s Plastics Boom,” The Nation

- Reading: Tim Dickinson, “How Big Oil and Big Soda kept a global environmental calamity a secret for decades,” Rolling Stone Magazine

- Reading: Sharon Lerner, “The Plastics Industry’s Long Fight to Blame Pollution on You,” Intercept

- Reading: Rebecca Leber, “Your Plastic Addiction Is Bankrolling Big Oil,” Mother Jones

- Video: Plastic Wars

Please watch Plastic China

Please answer the questions below referencing the film and your readings. Limit your answers to 150 to 400 words per question.

Explain the global impact of plastic pollution.

How would you evaluate the cost of plastic production?

Of the stakeholders: consumers, producers, government, who is most responsible for action related to plastics and the promotion of cradle to cradle products? Why? How can the change be implemented? How do you reconcile this with the present focus of economic growth (GDP based model)?

Topic 4: Discussion Promoting Sustainable Consumption

This week we are addressing lifecycle impacts of a very common product, plastic. The product incorporates many elements of environmental assessment: it has an ecological footprint, it is manufactured from a nonrenewable resource, it contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and it has adverse impacts to animal health, while the impact to the environment from waste disposal and manufacturing along with human health are emerging. How plastic became so ubiquitous is tied to a consumer-based economic model that only captures the prices paid not the externalities and does not weigh the cost to benefit of product deployment. Arguably, the market veil and incorrect perceptions of freedom may be a significant aspect of consumer behavior. In this discussion post use the readings from this week to develop a policy to eliminate plastic use. How would you go about it and who would you target? What types of outreach would be needed and how would you measure success? Is plastic the issue with plastic or is it something else (i.e. resource used, environmental impact, human health)?

July 11, 2017 by Steven Gorelick

A friend of mine from India tells a story about driving an old Volkswagen beetle from California to Virginia during his first year in the United States. In a freak ice storm in Texas he skidded off the road, leaving his car with a cracked windshield and badly dented doors and fenders. When he reached Virginia he took the car to a body shop for a repair estimate. The proprietor took one look at it and said, “it’s totaled.” My Indian friend was bewildered: “How can it be totaled? I just drove it from Texas!”

My friend’s confusion was understandable. While “totaled” sounds like a mechanical term, it’s actually an economic one: if the cost of repairs is more than the car will be worth afterwards, the only economically ‘rational’ choice is to drive it to the junkyard and buy another one.

In the ‘throwaway societies’ of the industrialized world, this is an increasingly common scenario: the cost of repairing faulty stereos, appliances, power tools, and high-tech devices often exceeds the price of buying new. Among the long-term results are growing piles of e-waste, overflowing landfills, and the squandering of resources and energy. It’s one reason that the average American generates over 70% more solid waste today than in 1960.[1] And e-waste – the most toxic component of household detritus – is growing almost 7 times faster than other forms of waste. Despite recycling efforts, an estimated 140 million cell phones – containing $60 million worth of precious metals and a host of toxic materials – are dumped in US landfills annually.[2]

Along with these environmental costs, there are also economic impacts. Not so long ago, most American towns had shoe repair businesses, jewelers who fixed watches and clocks, tailors who mended and altered clothes, and ‘fixit’ businesses that refurbished toasters, TVs, radios, and dozens of other household appliances. Today, most of these businesses are gone. “It’s a dying trade,” said the owner of a New Hampshire appliance repair shop. “Lower-end appliances which you can buy for $200 to $300 are basically throwaway appliances.”[3] The story is similar for other repair trades: in the 1940s, for example, the US was home to about 60,000 shoe repair businesses, a number that has dwindled to less than one-tenth as many today.[4]

One reason for this trend is globalization. Corporations have relocated their manufacturing operations to low-wage countries, making goods artificially cheap when sold in higher-wage countries. When those goods need to be repaired, they can’t be sent back to China or Bangladesh – they have to be fixed where wages are higher, and repairs are therefore more expensive. My friend was confused about the status of his car because the opposite situation holds in India: labor is cheap and imported goods expensive, and no one would dream of junking a car that could be fixed.

It’s tempting to write off the decline of repair in the West as collateral damage – just another unintended cost of globalization – but the evidence suggests that it’s actually an intended consequence. To see why, it’s helpful to look at the particular needs of capital in the global growth economy – needs that led to the creation of the consumer culture just over a century ago.

When the first Model T rolled off Henry Ford’s assembly line in 1910, industrialists understood that the technique could be applied not just to cars, but to almost any manufactured good, making mass production possible on a previously unimaginable scale. The profit potential was almost limitless, but there was a catch: there was no point producing millions of items – no matter how cheaply – if there weren’t enough buyers for them. And in the early part of the 20th century, the majority of the population – working class, rural, and diverse – had little disposable income, a wide range of tastes, and values that stressed frugality and self-reliance. The market for manufactured goods was largely limited to the middle and upper classes, groups too small to absorb the output of full throttle mass production.

Advertising was the first means by which industry sought to scale up consumption to match the tremendous leaps in production. Although simple advertisements had been around for generations, they were hardly more sophisticated than classified ads today. Borrowing from the insights of Freud, the new advertising focused less on the product itself than on the vanity and insecurities of potential customers. As historian Stuart Ewen points out, advertising helped to replace long-standing American values stressing thrift with new norms based on conspicuous consumption. Advertising, now national in scope, also helped to erase regional and ethnic differences among America’s diverse local populations, thereby imposing mass tastes suited to mass production. Through increasingly sophisticated and effective marketing techniques, Ewen says, “excessiveness replaced thrift as a social value”, and entire populations were invested with “a psychic desire to consume.” [5]

In other words, the modern consumer culture was born – not as a response to innate human greed or customer demand, but to the needs of industrial capital.

During the Great Depression, consumption failed to keep pace with production. In a vicious circle, overproduction led to idled factories, workers lost their jobs, and demand for factory output fell further. In this crisis of capitalism, not even clever advertising could stimulate consumption sufficiently to break the cycle.

In 1932, a novel solution was advanced by a real estate broker name Bernard London. His pamphlet, “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence” applauded the consumerist attitudes that advertising created during the 1920s, a time when “the American people did not wait until the last possible bit of use had been extracted from every commodity. They replaced old articles with new for reasons of fashion and up-to-dateness. They gave up old homes and old automobiles long before they were worn out.” [6] In order to circumvent the values of thrift and frugality that had resurfaced during the Depression, London argued that the government should “chart the obsolescence of capital and consumption goods at the time of their production… After the allotted time had expired, these things would be legally ‘dead’ and would be controlled by the duly appointed governmental agency and destroyed.”[7] The need to replace these ‘dead’ products would ensure that demand would forever remain high, and that the public – no matter how thrifty or satisfied with their material lot – would continue to consume.

London’s ideas did not catch on immediately, and the Depression eventually ended when the idle factories were converted to munitions and armaments production for World War II. But the concept of planned obsolescence did not go away. After the War its biggest champion was industrial designer Brooks Stevens, who saw it not as a government program but as an integral feature of design and marketing. “Unlike the European approach of the past where they tried to make the very best product and make it last forever,” he said, “the approach in America is one of making the American consumer unhappy with the product he has enjoyed the use of…, and [making him want to] obtain the newest product with the newest possible look.”[8]

Brooks’ strategy was embraced throughout the corporate world, and is still in force today. Coupled with advertising aimed at making consumers feel inadequate and insecure if they don’t have the latest products or currently fashionable clothes, the riddle of matching consumption to ever-increasing production was solved.

The constant replacement of otherwise serviceable goods for no other reason than “up-to-dateness” is most clear at the apex of the garment industry, tellingly known as the “fashion” industry. Thanks to a constant barrage of media and advertising messages, even young children fear being ostracized if they wear clothes that aren’t “cool” enough. Women in particular have been made to feel that they will be undervalued if their clothes aren’t sufficiently trendy. It’s not just advertising that transmits these messages. One of the storylines in an episode of the 90s sit-com “Seinfeld”, for example, involves a woman who commits the faux pas of wearing the same dress on several occasions, making her the object of much canned laughter.[9]

Obsolescence has been a particularly powerful force in the high-tech world, where the limited lifespan of digital devices is more often the result of “innovation” than malfunction. With computing power doubling every 18 months for several decades (a phenomenon so reliable it is known as Moore’s Law) digital products quickly become obsolete: as one tech writer put it, “in two years your new smartphone could be little more than a paperweight”.[10] With marketers bombarding the public with ads claiming that this generation of smartphone is the ultimate in speed and functionality, the typical cell phone user purchases a new phone every 21 months.[11] Needless to say, this is great for the bottom line of high-tech businesses, but terrible for the environment.

Innovation may be the primary means by which high-tech goods are made obsolete, but manufacturers are not above using other methods. Apple, for example, intentionally makes its products difficult to repair except by Apple itself, in part by refusing to provide repair information about its products. Since the cost of in-house repair often approaches the cost of a new product, Apple is assured of a healthy stream of revenue no matter what the customer decides to do.

Apple has gone even further. In a class-action lawsuit against the company, it was revealed that the company’s iPhone 6 devices were programmed to cease functioning – known as being “bricked” – when users have them repaired at unauthorized (and less expensive) repair shops. “They never disclosed that your phone could be bricked after basic repairs,” said a lawyer for the complainants. “Apple was going to … force all its consumers to buy new products simply because they went to a repair shop.”[12]

In response to this corporate skulduggery, a number of states have tried to pass “fair repair” laws that would help independent repair shops get the parts and diagnostic tools they need, as well as schematics of how the devices are put together. One such law has already been passed in Massachusetts to facilitate independent car repair, and farmers in Nebraska are working to pass a similar law for farm equipment. But except for the Massachusetts law, heavy lobbying from manufacturers – from Apple and IBM to farm equipment giant John Deere – has so far stymied the passage of right-to-repair laws.[13]

From the grassroots, another response has been the rise of non-profit “repair cafés”. The first was organized in Amsterdam in 2009, and today there are more than 1,300 worldwide, each with tools and materials to help people repair clothes, furniture, electrical appliances, bicycles, crockery, toys, and more – along with skilled volunteers who can provide help if needed.[14] These local initiatives not only strengthen the values of thrift and self-reliance intentionally eroded by consumerism, they help connect people to their community, scale back the use of scarce resources and energy, and reduce the amount of toxic materials dumped in landfills.

At a more systemic level, there’s an urgent need to rein in corporate power by re-regulating trade and finance. Deregulatory ‘free trade’ treaties have given corporations the ability to locate their operations anywhere in the world, contributing to the skewed pricing that makes it cheaper to buy new products than to repair older ones. These treaties also make it easier for corporations to penetrate not just the economies of the global South, but the psyches of their populations – helping to turn billions of more self-reliant people into insecure consumers greedy for the standardized, mass-produced goods of corporate industry. The spread of the consumer culture may help global capital meet its need for endless growth, but it will surely destroy the biosphere: our planet cannot possibly sustain 7 billion people consuming at the insane rate we do in the ‘developed’ world – and yet that goal is implicit in the logic of the global economy.

We also need to oppose – with words and deeds – the forces of consumerism in our own communities. The global consumer culture is not only the engine of climate change, species die-off, ocean dead zones, and many other assaults on the biosphere, it ultimately fails to meet real human needs. The price of the consumer culture is not measured in the cheap commodities that fill our homes and then, all too soon, the nearest landfill. Its real cost is measured in eating disorders, an epidemic of depression, heightened social conflict, and rising rates of addiction – not just to opioids, but to ‘shopping’, video games, and the internet.

It’s time to envision – and take steps to create – an economy that doesn’t destroy people and the planet just to satisfy the growth imperatives of global capital.

- Reading: Paul M. Gregory, “A Theory of Purposeful Obsolescence,” Southern Economic Journal

- Reading: Joseph Guiltinan, “Creative Destruction and Destructive Creations: Environmental Ethics and Planned Obsolescence,” Journal of Business Ethics

- Reading: Andrew Szasz, “Consumption,” NYU Press

- Reading: Rob Weterings, Ton Bastein, Arnold Tukker, Michel Rademaker and Marjolein de Ridder, “Resource Constraints,” Amsterdam University Press

- Video: The Lightbulb Conspiracy

Please watch The Lightbulb Conspiracy

How does the subject of this film align with GDP/economic growth?

Did the subject disturb you? If so, how? Explain.

What was the trade-off to sustainability as depicted in the film?

Has the product lifecycle depicted in the film been normalized? Explain and address how this has affected the perception of being able to achieve sustainability.

Topic 5: Discussion Planned Obsolescence

This week we have focused on planned obsolescence. It is clear from the readings that planned obsolescence is resource intensive but though it is designed for the dump, it is a credited process in how we define economic growth. For our discussion, I would like you to think about how the components (individuals (consumers), firms (producers) and the government of our economy work in silo and appear to have no alignment with respect to the benefit of the whole (i.e. firms are focused on profit; consumers are self-interested and focused on gratification; and government is focused on the interests of the constituents that are the most powerful). How can these groups work together to define an outcome to benefit all? What are the limitations of such a discussion? Are there examples of success? How does cultural context affect the potential for solution? How does the definition of economic growth provide an obstacle?

Building on Phase Two of your project, create a presentation that addresses at minimum the following questions. Please be as comprehensive as possible using information available from credible public sources.

- Describe the product

- Define the stages you are assessing and explain what you will highlight in each

- Discuss each stage separately and highlight the market and non-market costs attributable to each

- Address how much of the product you consume and how this consumption affects your resource footprint

- Discuss whether the market price for the product is justified–what are the qualitative costs/benefits (i.e. externalities, health/nutrition impacts)

- Is the product sustainable? Why? Why not?

- Should consumption be limited?