When it comes to conveying the realities of climate change, adding more information may not always help—this was the takeaway message from scholars and artists at the NULab’s recent “Climate Change/Crisis/Creativity” conference. The conference was a collaborative event co-hosted with the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, the Humanities Center, the Department of English, and the Global Resilience Institute. Layering on more information doesn’t always help because climate change can be too large of an issue for people to contextualize or act on. For instance, Carolina Aragón uses public art, such as her Future Waters piece, to demonstrate how high waters are predicted to rise. The installation, on the East Boston Greenway, visualized projected water levels in 2030 and 2070—2.3 feet and 5.5 feet—with raised platforms and solar-powered beams to simulate water. Aragón described her surprise with the many different ways people engaged with her piece both in person and through social media, including one woman who posed for a photograph next to the installation and posted online that the projected water levels would be high enough to cover her head. As Aragón explained, the personal and physical connections that people made with the installation were effective at communicating the impact of climate change on individual lives.

Other speakers at the event discussed helping people make a personal connection with climate change, including the conference’s Peter Burton Hanson Memorial Lecturer Bethany Wiggin. Wiggin underscored the need to address climate change locally through her discussion of several community-based efforts organized by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities. The conference also included an exhibition of posters by LCAart that contextualize big-picture issues with everyday images, such as a depiction of how much waste is generated by a single styrofoam coffee cup, showing the size of the cup proportional to its environmental impact. As all of these examples indicate, context and a personal connection can have an enormous impact on how people understand climate change.

Elizabeth Maddock Dillon opened the event with a discussion of how interdisciplinary connections enable more effective work on climate change. Next were two sessions of lightning talks featuring the work of Northeastern faculty and staff. The first session included talks from John Wihbey, Shalanda Baker, Dietmar Offenhuber, Jennie Stephens, and Daniel O’Brien, who work in journalism, public policy and urban affairs, law, and criminology. These seven-minute presentations covered topics including smart cities and the impact of renewable energy development on indigenous communities. Consensus and collaboration emerged as a key theme in these talks, as in Shalander Baker’s (Law School) discussion of indigenous communities in Mexico. Baker argued that people directly affected by environmental policy must have a voice in its creation.

The second session included talks from Laura Kuhl, Kyla Van Maanen, Sara Wylie, and Brian Helmuth, who work in international affairs, marine and environmental sciences, and health sciences. These talks highlighted the diverse approaches to climate change being studied at Northeastern–ranging from the collection and preservation of data to the environmental impact of underwater art installations–while continuing to underscore the need for local collaborations. Brian Helmuth’s work in the Iraqi Marshlands, for example, prioritizes building trust with communities impacted by climate change. The Iraqi Marshlands were destroyed in what Helmuth terms an ‘ecocide,’ which caused the widespread deaths and displacement of indigenous people—a genocide caused by ecocide. Helmuth’s presentation described strategies for mitigating this destruction in partnership with Iraqi researchers and community members.

Bethany Wiggin, University of Pennsylvania, co-founder of the Data Refuge project delivered the conference’s Peter Burton Hanson Memorial Lecture. After an introduction by Sara Wylie, who also works on Data Refuge, Wiggin spoke on “Climate Change and Pedagogy: Experiential and Embodied Learning for the Academy and Beyond.” Wiggin explored how climate change influences what we teach and learn. Wiggin is the Founding Director of the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities and she shared a variety of student and faculty projects from the program, focusing on the Schuylkill Research Corps, Rising Waters, and Data Refuge projects. All three projects share important connections to the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania as well as a consciously trans-disciplinary nature—they are placed-based and public-facing.

The Schuylkill Research Corps is a living history project, collecting research materials and engagement projects focused on Philadelphia’s urban waters. The project attempts to bolster public research and learning through tours, exhibits, and even activities for children. The Rising Waters initiative is a “multidisciplinary research project situated in the former wetlands of Philadelphia and Mumbai.” Using ethnographic and historical research, the project works with local communities to produce alternative visions of the two cities’ future. The Data Refuge project began with a question posed by a student in the wake of the 2016 election: how might climate change deniers endanger federal environmental data? The goal of the project is data preservation and protection, especially populations that are not always included in discussions within the academy.

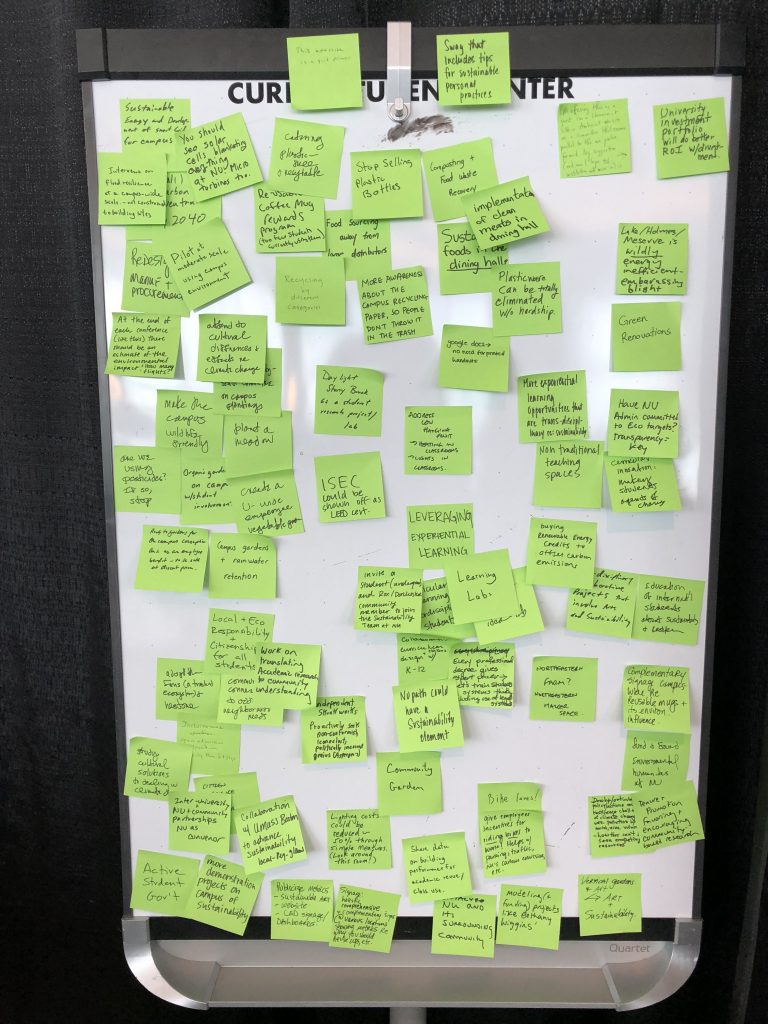

During the lunch hour, the Sustainability and Resilience Advisory Team at Northeastern led a hands-on working session that asked attendees to share their thoughts on how Northeastern is addressing climate change. The Advisory Team led a participatory exercise to identify actions at NU that are working, those that aren’t working as well, and new ideas that have potential. The exercise generated a multitude of ideas that have potential, including calls for the university to stop selling plastic water bottles and for professors to rely on Google Docs to eliminate paper waste from handouts, as well as calls for the university to divest from fossil fuels.

The conference concluded with presentations from three artists, Carolina Aragón, Geoffrey Hudson, and Sarah Kanouse. Carolina Aragón, an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at UMASS Amherst, discussed her public artwork, including the High Tide and Future Waters installations, both located in Boston. Composer Geoffrey Hudson discussed his process for creating “A Passion for the Planet,” a large-scale work for chorus and orchestra focusing on the pains and perils of climate change. Hudson explained that he was careful not to write a requiem for the planet, instead striving to produce a piece that encourages action and engagement from the public. Sarah Kanouse, an Associate Professor of Art + Design at Northeastern, performed an excerpt from her one-woman show “My Electric Genealogy,” framed around the 99 years between the births of her grandfather and her daughter. In the piece, Kanouse posits that her young daughters’ life has been shaped by environmental milestones, as much as by developmental milestones, contextualizing the imminent danger of a changing climate. She connects the larger issue of climate change with her family story, engaging with both physical infrastructures, such as power lines and “infrastructures of feeling.”

The “Climate Change/Crisis/Creativity” conference provided an interdisciplinary forum that emphasized the important roles of connections, personal networks, and community in moving climate change work forward. Participants expressed hope that the conference will itself create connections and support new communities in working to address climate change.